Global Courant 2023-05-01 15:00:18

“God Mode”, for those who aren’t gamers, is a mode of operation (or cheat) built into some types of games that are based around shooting things. In God mode, you are invulnerable to damage and never run out of ammo.

Of course, there is no God mode in real life, but the world’s military organizations are very interested in weapons that promise such a thing – lasers and other “directed energy weapons.” For example, the US government spend nearly $1 billion annually on targeted energy projects.

Australia is not immune to the appeal. The Power structure plan 2020 called for a directed energy weapon system “capable of defeating armored vehicles up to and including main battle tanks”.

In March this year, Deputy Prime Minister Richard Marles launched the new Australian startup AIM Defense targeted energy test range on the outskirts of Melbourne. The Defense Science and Technology group announced this in April a A$13 million (US$8.6 million) deal with British defense technology company QinetiQ to develop a prototype defense laser.

And directed energy technology is a priority in the new A $3.4 billion Advanced Strategic Capabilities Accelerator (ASCA) program.

A directed energy weapon concentrates large amounts of electromagnetic energy on a distant target. This energy can be in the form of light (a laser), but microwaves or radio waves can also be used.

For the sake of brevity, we’re focusing here on laser-based directed energy weapons, but many of the arguments apply to the other types as well.

Depending on how much energy is directed at the target, these weapons can damage the delicate electronic systems that control devices and the people operating them, or melt or incinerate more powerful hardware.

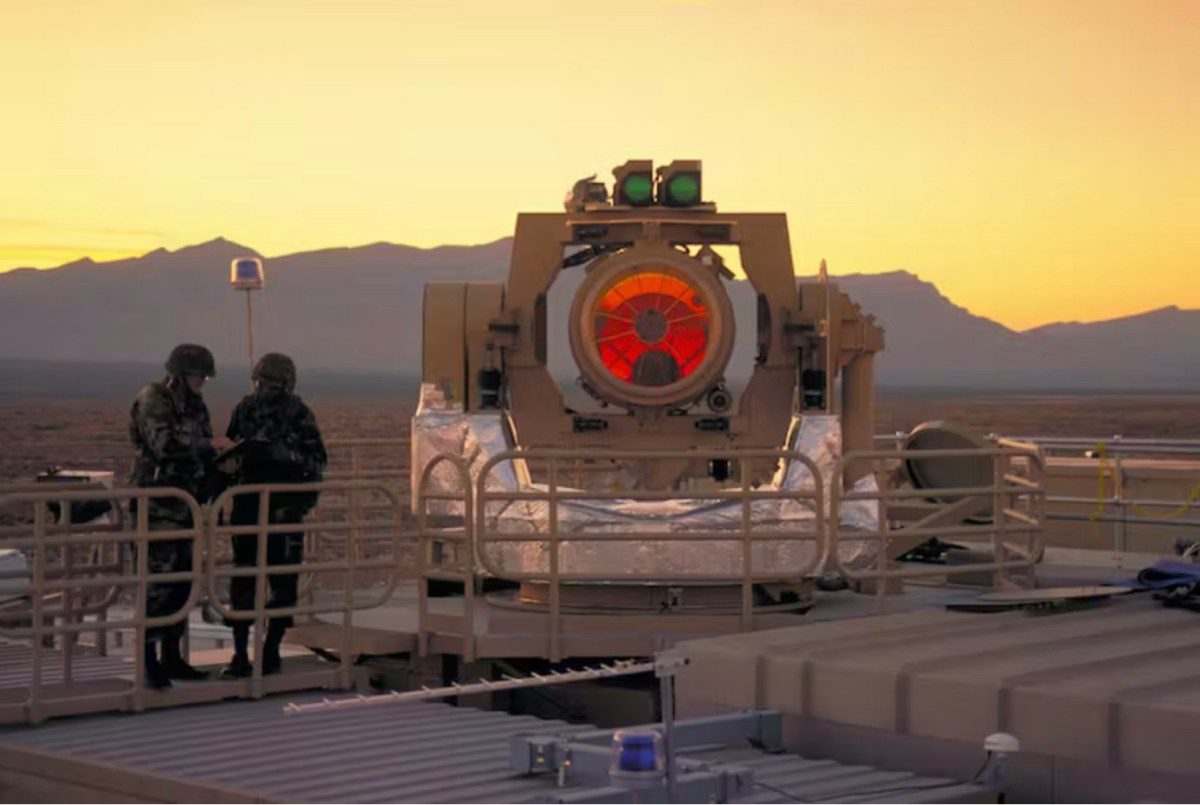

The US tested experimental laser weapon systems in the 1980s. Photo: AP via The Conversation

Because electromagnetic waves travel at the speed of light, they are much faster than even the fastest traditional weapons.

Take a hypersonic missile traveling at ten times the speed of sound to a target 10 kilometers away. It would have moved only about 4 inches by the time the focused light energy from a high-powered laser would have reached the target.

Plus, because these guns project light instead of ammo, they will never run out of ammo. This also means that ammunition does not have to be made in a factory and transported to the weapon.

Directed energy is unaffected by gravity like rockets and bullets, so it moves in a straight line. This makes aiming and targeting easier and more reliable.

And because directed energy weapons deal damage by heating up a target area, they are less likely to hit nearby objects or send shrapnel flying around.

While directed-energy weapons have all of these advantages over conventional weapons, usable weapons have proven to be difficult to build.

One problem laser weapons face is the sheer amount of power required to destroy useful targets such as missiles. Destroying something this size would require lasers with hundreds of kilowatts or even megawatts of power. And these devices are only about 20% efficient, so we would need five times as much power to run the device itself.

We’re well into the megawatt range here – that’s the kind of power consumed by a small town. For this reason, even portable devices with directed energy are very large.

(It was only recently that the US succeeded in making a relatively low-power 50 kW laser compact enough to fit on an armored vehiclealthough devices have been developed that work with power up to 300 kW.)

The US Directed Energy Maneuver-Short Range Air Defense, or DE M-SHORAD, is a 50 kW laser system mounted on an armored vehicle. Photo: Jim Sheppard / US Army through The Conversation

Also, all that heat has to be removed from the delicate optical equipment that produces the light very quickly, or else it will damage the laser itself. This has proved difficult, although laser technologies with more efficient heat transfer have gradually increased the amount of light energy that can be reliably produced.

Another side effect of dealing with such large amounts of energy is that any imperfections in the optical systems used to focus and direct the light can easily cause catastrophic damage to the laser system.

Nor is it easy to focus a laser on a spot the size of a 10 cent piece tens of miles away, through atmospheric turbulence and dust or rain. Add to this the difficulty of keeping the energy in the same location on a fast-moving target for tens of seconds, and the practical difficulties become apparent.

That said, the technologies to overcome all these obstacles continue to improve.

But suppose all the technical problems of directed energy weapons are overcome. Even then, to produce them in large quantities, we will face significant supply chain and infrastructure challenges.

There are companies in Australia with the expertise to make such devices. However, developing and mass-producing directed energy weapons requires an industrial capacity to manufacture the necessary laser diodes and high-performance optics, which does not exist in Australia.

In order to have “sovereign capability” – being able to produce these weapons without relying on foreign inputs – we will have to develop such industries.

This is a time-consuming and expensive investment in national infrastructure. In peacetime, it is relatively easy to source the raw materials for a directed energy weapon from abroad, but in a full-scale conflict, countries that can produce these devices are likely to produce them for their own needs.

The potential military benefits of directed energy weapons, and the consequences if an adversary has them, mean that Australia and many other countries will continue to be interested in developing them.

But as recent policy decisions on nuclear submarines have shown, it is no easy task to rapidly develop an industrial capability in technologies that our industrial base has so far largely ignored.

Sean O’Byrne is Associate Professor, Deputy Head (Research), School of Engineering and Information Technology, UNSW Canberra, UNSW Sydney

This article has been republished from The conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Similar:

Loading…