Global Courant 2023-05-28 00:42:06

This article is part of Overlooked, a series of obituaries about notable people whose deaths, beginning in 1851, went unreported in The Times.

In July 1929, 12 chess players gathered at Chatham House School, a venerable institution in Ramsgate, England, to contest the British Championship. The field included several well-known masters, as well as a player who stood out from the crowd because he was not from England, but from the jewel of the British Empire: India.

His name was Sultan Khan.

It’s doubtful the other competitors knew much about him, and they probably didn’t see him as a major threat. At the time, Europe was the center of the chess world, and although Khan had won the All-India Championship the year before, it was most likely against an inferior level of competition compared to what he would face in the upcoming tournament.

In addition, there were differences in the rules of chess across the subcontinent. For example, pawns could not move two squares on their first turn, and there was no comparable castling rule. Instead, the king can move like a knight with one move during the game. The need to adapt to how the game was played in Europe left Khan significantly handicap, especially in the early stages of games.

Growing up in India under British rule, Khan also had little or no access to chess books, so he knew next to nothing about game starting theory – knowledge that his rivals possessed.

None of that stopped him. Khan won the championship convincingly, recording wins in more than half of his matches and only losing once. This marked the start of a whirlwind four-year period where Khan took on the world’s best players and more than held his own.

Despite his first name, Khan was not royalty. According to a 2020 article by Ather Sultan, his eldest son, and Atiyab Sultan, one of his granddaughters, written for the Pakistani news site Dawn, Khan was born in 1903 (some other sources say 1905) in Khushab, a city in the Punjab region of modern-day Pakistan . His family consisted of landowners and pirs, or Sufi religious guides.

Khan learned to play chess from his father, Mian Nizam Din, when he was young, and he was the best player in Punjab by the time he was 21. A wealthy landowner, Sir Umar Hayat Khan Tiwana, hired him to develop a chess team. , for which he received a monthly allowance and room and board. When Sir Umar went to live in London in 1929 to attend the Roundtable Conferences on Parliamentary Reform in India, Khan went with him.

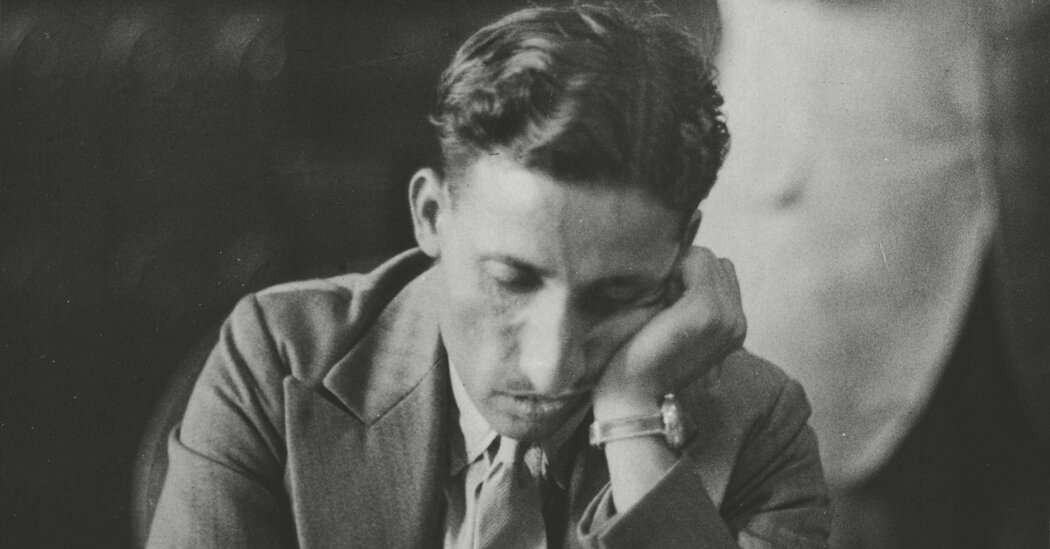

Sitting at a chess table, Khan made a striking figure with his thin face, wide forehead and sharp eyes. He often wore a white turban. He was imperturbable, almost disturbing. Regardless of the position on the board, his demeanor remained calm. David Hooper and Kenneth Whyld in their book “The Oxford Companion to Chess” (1984) thought that “the player who applies the greatest concentration should win”, wrote David Hooper and Kenneth Whyld in their book “The Oxford Companion to Chess” (1984).

After his victory at the British Championship, Khan briefly returned to India, but he was back in England in May 1930 and began receiving invitations to compete in elite tournaments. He quickly proved to be one of the best players in the world.

He came fourth in a tournament in Scarborough, England, in June and July 1930, in which, in addition to the best English players, five of the strongest players on the European continent took part.

He then represented England as the top player at the Third Chess Olympiad in Hamburg, Germany, a gathering of the best teams from the best chess nations in the world. Khan scored nine wins against four losses and four draws.

After Hamburg, Khan took part in an invitation-only tournament in Liège, Belgium, featuring some of Europe’s best players. This time he came second, behind Savielly Tartakower from Poland. A few months later Khan defeated Tartakower in a 12 match match.

At an elite annual tournament in Hastings in late 1930 and early 1931, Khan finished third behind Max Euwe, who would become world champion in 1935, and José Raúl Capablanca, a former world champion who was still regarded by many as the world’s best player. . During the match, Khan caused a sensation by beating Capablanca, slowly beating him in a style reminiscent of Capablanca himself.

At the 1931 Chess Olympiad in Prague, Khan again led the England team and had another excellent result, with eight wins, seven draws and two losses. His wins included wins against Akiba Rubinstein and Salomon Flohr, two of the top 10 players in the world, and his draws included matches against Alexander Alekhine, the reigning world champion, and Efim Bogolyubov, who had played Alekhine twice for the title.

Khan failed to defend the British title in 1931, finishing tied for second place and finishing the year by finishing fourth at the 1931–32 Hastings Tournament.

In 1932 he came third in a tournament in London with Alekhine, Flohr and Tartakower. After narrowly losing a match to Flohr, Khan played in the Cambridge Premier League, beating most of Britain’s top players, including Conel Hugh O’Donel Alexander, the Irish cryptologist who worked with Alan Turing during World War II. would collaborate on the German Enigma machine.

Khan ended the year by finishing fourth in a tournament in Bern, Switzerland, which included Alekhine, Euwe, Flohr and Bogoljubov; win the British Championship for the second time; and tied for third place at the 1932–33 Hastings Tournament.

Khan’s last competitive year, 1933, was much slower. The only major events he participated in were the Olympiad in Folkestone, England, again as England’s top player, and the British Championship, where he won the title for the third time.

In December 1933, Sir Umar decided to return to India, and Khan returned with him, as it was too expensive to stay. Khan was apparently happy to leave England. He disliked the cold, rainy weather and suffered from malaria and a constant cold and sore throat. Ghulam Fatima, a chess player who worked for Sir Umar in his London household and who won the British Women’s Championship in 1933, told Hooper and Whyld for their book that when Khan left England he “felt as if he had been released from prison . ”

Back in India, Khan played one match in 1935, against VK Khadilkar, beating him solidly winning nine matches and drawing one.

And that was it. He stopped playing, at least in competitions.

In a short documentary broadcast on British television in the late 1970s, Ather Sultan said that he once asked his father why he had not tried to play for the world championship, and that his father said that at the time the challenger had placed a stake of 2,000 pounds (about $ 230,000 in today’s dollars), which he didn’t have.

According to the Dawn article, Khan married and had five sons and six daughters. He spent the rest of his life cultivating his farmland before he died in Sargodha on April 25, 1966.

While his children and grandchildren were learning to play chess, they mostly pursued other careers. Ather Sultan said his father “told them to do something more useful with their lives.”

There were no official rankings when Khan played, but according to Chess Metrics, a widely respected website that has compiled backdated rankings over 200 years ago, he was No. 6 or No. 7 in the world for the last two years of his life. chess career. Hooper and Whyld surmised that Khan overcame his lack of opening knowledge because he was one of the best players in the world in the midgame phase and one of the two or three best players in the endgame phase, along with Capablanca.

A biography, “Black & White: The Official Biography of Chess Champion Sultan Khan,” by Dr. Sultan and Ather Khan, will be published in June.

In the Dawn article, his son and granddaughter ruefully noted that many of the players Khan defeated were International Chess Federation anointed grandmasters and international masters when the federation began awarding those titles in 1950, though most of them lost their primes had achieved. But Khan was never recognized in the same way.

Perhaps the best nickname he could have received, however, came from a respected contemporary. Often regarded as one of the greatest naturals of all time, Capablanca described Khan in his writings with a word he almost never used: “genius.”