Global Courant 2023-05-11 03:22:39

Watching a harbor porpoise emerge from a vaquita marina above the ocean’s surface is a real emotional rollercoaster, says a Canadian scientist who tracks the elusive sea creatures.

“It’s one of the most amazing and fantastic — yet sad at the same time — experiences when you see one of the rarest mammals on Earth,” Anna Hall, a Vancouver Island marine zoologist, told As It Happens host Nil Köksal.

It’s amazing, she says, because every vaquita sighting is proof that they still exist. They are listed as critically endangered, and the last time scientists surveyed their habitat in 2021, they recorded likely sightings of between five and 13.

But every time she sees one, Hall says “there’s a sadness that accompanies it,” as she’s reminded of expeditions she undertook 20 years ago, when hundreds of tiny critters swam off the coast of Mexico.

Hall, who works for Sea View Marine Sciences and the Porpoise Conservation Society, is part of a new expedition to search for the rare and elusive creatures in their only habitat: the Sea of Cortez off the coast of Mexico.

The expedition is being conducted in collaboration with the Mexican government and the conservation organization Sea Shepherd. Their goal is to determine if there are any vaquitas left since the last survey of their dwindling population two years ago.

“Before I left Canada I was asked why I would do something like this when the chances of seeing them are so slim,” Hall said. “And my answer was, well, because I care so much about these creatures and the other creatures in our ocean.”

Between May 10 and May 27, the group will sail the Sea of Cortez in a Sea Shepherd ship and a Mexican boat, using binoculars, sights and acoustic monitors to pinpoint the location of vaquitas.

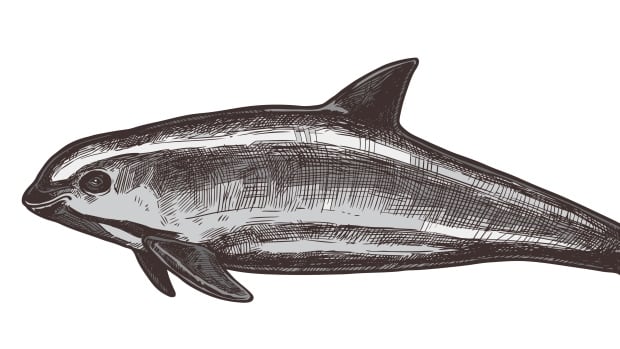

This undated file photo from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration shows a vaquita porpoise. (Paula Olson/NOAA/The Associated Press)

Vaquitas are cetaceans that grow to about 140 to 150 centimeters in length. Because they are so rare, there aren’t many good photos of them. But Hall said they look like little dolphins with black circles around their mouths and eyes.

“They’re incredibly cute,” she said, commenting on the “little sniffing noises” they make when they come up for air.

“They are one of the most endearing creatures on the planet, and I am truly honored and privileged to be here on this expedition.”

What kills the vaquitas?

This is reported by the International Union for Conservation of Naturewhich collects international data on species populations, there were as many as 567 vaquitas in 1997. By 2008, that number had dropped to 245 — a loss of 57 percent.

Hall says there were “maybe 10” by 2021. It is difficult to say how many there are, because they are small and can often be seen from afar. It can be difficult to tell if a sighting is indeed a vaquita, how many there are, or if you’ve seen the same one more than once.

The reason for their dramatic decline, Hall says, is simple. They become entangled in gillnets – large walls of nets used by local fishermen.

Gillnet fishing has been illegal in Mexico since 2017 in direct response to dwindling numbers of vaquitas, but Hall says the industry has continued to flourish illegally.

The vaquitas are often trapped in illegal gillnets. (NOAA)

The vaquitas are not targeted by the fishermen. They happen to share a habitat with totoaba, a fish whose swim bladder is considered a delicacy in China and can fetch thousands of dollars per kilo.

Can they bounce back?

Sea Shepherd is working with the Mexican Navy in the Gulf to deter illegal fishing in the only area where vaquitas were last seen.

Fishing is prohibited in the area. However, illegal fishing boats are regularly seen there during scientific expeditions.

Sea Shepherd chairman Pritam Singh said a combination of patrols and the Mexican Navy’s plan to sink concrete blocks with hooks to ensnare illegal nets will reduce the number of hours fishing boats spend in the restricted zone by 79 percent by 2022 . to the previous year.

“The past 18 months have been incredibly impressive and encouraging,” he said.

A mother vaquita and her calf. (Tom Jefferson)

But Hall says they won’t know for sure if these efforts work until they head out to the ocean to look for vaquitas.

Any sighting will be a relief, she said. But the best case scenario is if they see a mother and calf.

“That would tell us that biologically within the population we still have males and females,” she said.

But the only way to ensure their survival is to protect their habitat, she said. That’s because they can’t survive in captivity.

“Their bodies cannot withstand confinement,” she said. “They’re just too fragile.”

Activists and artists held a mournful, dirge-like procession for the critically endangered vaquita porpoise in Mexico City in 2018. (Marco Ugarte/The Associated Press)

She says vaquita conservation is frustrating work because it’s endlessly challenging, even though it should be simple.

“All we need is a place in the ocean, in the habitat of the vaquita, that is free of the nets,” she said.

“In some ways it’s a very simple solution, but it’s one of the most complicated conservation challenges we have on this planet.”