Global Courant 2023-05-09 11:58:29

Suddenly, China is inundated with talk of deflation.

Slowing consumer price increases are fueling a conversation no government wants. Price increases slowed to a negligible 0.3% in April on an annual basis, compared to 0.7% in March. Meanwhile, we see producer prices falling by another 3.0% in April, following a 2.5% fall in March.

These are numbers for which Jerome Powell could commit murder in Washington. The chairman of the Federal Reserve is wracked by the worst US inflation in 40 years. And the stalemate on Capitol Hill is preventing the US from addressing supply-side inflation, over which the Fed has little influence.

However, for many, despite the reopening of the economy due to Covid-19, low prices in China are ringing alarm bells. Loud too.

“Deflationary risks could tip the balance in favor of more easing from the People’s Bank of China,” said Carlos Casanova, an economist at Union Bancaire Privée.

Yet another argument is worth considering: that China is experiencing disinflation, not outright deflation, and that there are more positives than negatives to the phenomenon.

Instead of problems coming, “this indicates that China’s economic transformation is accelerating and that we are ushering in a digital economy and high-tech transformation,” argues economist Chen Fengying, former director of the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations.

Chen points to the 5.1% increase in fixed asset investment in the first quarter year-over-year. Investments in high-tech industries, meanwhile, rose by 16%. For the e-commerce services sector, investments increased by almost 52%.

Does this indicate “remarkable optimization of China’s economic structure” and “industrial transformation and upgrading”, as economists like Wan Zhe of Beijing Normal University claim?

Increased productivity

Time will tell. It is quite possible that the strong downward pressure of technological change means higher productivity, not economic gloom.

Recent news from Alibaba Group may support the argument. At the end of April, the e-commerce giant’s cloud computing unit slashed prices by 50% amid increased competition.

It seems no coincidence that the move — one that could lure users from rivals like Tencent Holdings — comes as Alibaba works to break up the $214 billion empire founder Jack Ma has built. Is this positive evidence that increased technical efficiency is gaining momentum in Asia’s largest economy?

Economist Helen Qiao of BofA Global Research notes that “central bankers in China seemed to have little concern about deflation, judging by the PBOC’s quarterly monetary policy reports and minutes.”

Overall, she adds, “they expect inflationary pressures to increase as the output gap narrows in the second half of 2023, especially as a new credit cycle kicks in.”

Reforms in the private sector are needed

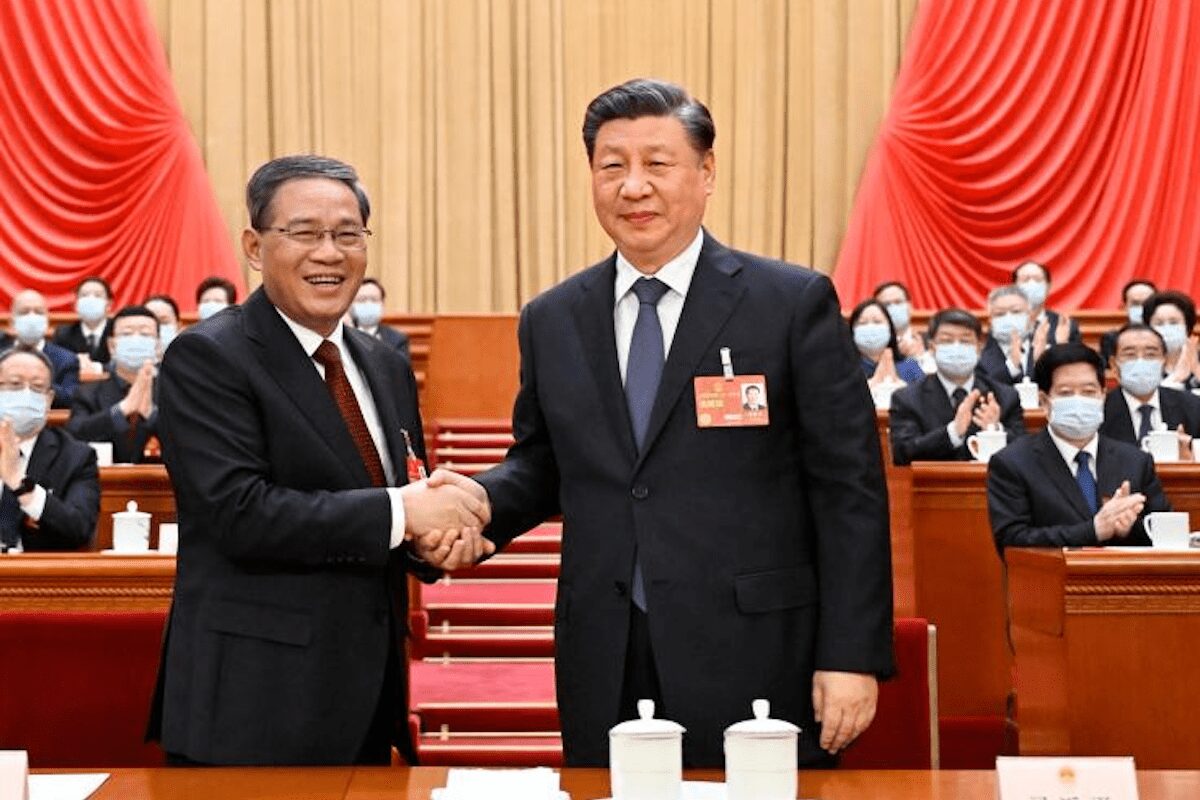

Again, only time will tell. But in the meantime, Chinese President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Qiang must accelerate reforms to create a larger and more vibrant private sector. This means prioritizing regulatory adjustment over aggressive incentives that could encourage bad behavior from local government officials and property developers.

In late March, Li visited the southern export metropolis of Guangdong to call for Chinese self-reliance on technology and plans to support the private sector. Li also met founders of tech “unicorn” startups.

As Bill Bishop, author of the Sinocism newsletter, summarizes: “One of the main themes of his journey: deepening reform and expanding ‘high-value’ opening; Food Safety; green development; regional connectivity between Guangdong, Hainan and the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area; management of water resources; rural revitalization; common prosperity; opportunities for foreign investors; manufacturing and accelerating the building of a modern industrial system supported by the real economy; real economy and self-reliance; indigenous development of nuclear technologies in ‘key areas’; Chinese modernization; and the importance of the ‘Xi Thought’ education campaign.”

The concern, says Bishop, is that this could only be remembered as a “propaganda list.” The final reference is to Xi’s vaguely defined political ideology, one being introduced into school curricula in the most populous country. It’s now up to Li to work out exactly what that means.

Li is thought to be pro-innovation and pro-startup since his days as governor of Zhejiang province. That’s where Alibaba’s headquarters are located, and Li was reportedly close to founder Ma. During his days as party boss in Shanghai, Li successfully lobbied Elon Musk to build a giant electric car factory in the city, the Tesla founder’s first overseas branch.

The hope is that Li’s rise to the top of power in Beijing is a signal that regulatory attacks on the high-tech sector are now a thing of the past, and that Xi’s efforts in recent years to prioritize growth in the state sector are reversed. to nurturing private enterprise. The question, of course, is how much leeway Xi will give his new No. 2 to make room for entrepreneurs to innovate and create high-paying jobs from scratch.

It is one thing for Communist Party officials to claim “unwavering” support for the private sector and make commitments “to further open China’s economy to the outside world,” says S&P Global Ratings economist Louis Kuijs. It is more important that the words are linked to action.

That may be one of the reasons that business confidence among private and foreign companies has lagged in recent months. Deteriorating relations between the US and China hardly help, especially in the context of Xi’s crackdown on the internet sector.

As Kuijs points out, there is “only so much China can do” to ease decoupling pressures. The answer, he says, is clear and deliberate steps to level the playing field for state-owned companies and both private and foreign companies.

The right mix would support China’s soft power and support Xi’s argument that Beijing deserves more say in global affairs. As the head of the International Monetary Fund, Kristalina Georgieva, puts it: “The strong upswing means China will account for about a third of global growth by 2023, providing a welcome boost to the global economy.”

Yet China’s work has definitely been undone. China’s post-Covid uptick in household consumption has often disappointed. Certainly, many are optimistic that the tide is turning. In March, for example, total retail sales of consumer goods rose 10.6% year-on-year.

“The combination of a steady rise in consumer confidence and the still-incomplete release of pent-up demand suggests to us that the consumer-led recovery still has room to spare,” said Oxford Economics economist Louise Loo.

At the same time, however, others argue that “the market’s current concerns about deflation largely reflect concerns about the strength and sustainability of the economic recovery,” said China Minsheng Bank economist Wen Bin. “After the optimization of epidemic prevention and control, the production side has essentially returned to pre-epidemic levels, but the momentum on the demand side is still weak.”

Global headwind

Weak global trends hardly help here. The cumulative fallout from the Powell Fed’s aggressive rate hikes continues to jeopardize the global banking system – from Silicon Valley Bank to Credit Suisse to First Republic Bank. In addition, US President Joe Biden’s increasing efforts to contain China’s role in world trade, finance and security are creating new headwinds.

As Christine Lagarde, head of the European Central Bank, said last week: “We are witnessing a fragmentation of the world economy into competing blocs, with each bloc trying to get as much of the rest of the world closer to its respective strategic interests as possible. draw and shared values. All this could have far-reaching implications for many areas of policy-making.”

As all these countercurrents test Xi’s economy, it is up to Beijing’s reformers to stay on track in recalibrating the engines of growth. While Premier Li’s office works on some supply-side upgrades, it will be up to the central bank to iron out cracks in China’s recovery.

China’s 4.5% annual growth rate in the first quarter was in line with “an optimistic full-year outlook for growth in China,” notes Goldman Sachs economist Hui Shan.

Meanwhile, exports increased by 8.5% in April, the second monthly increase in a row.

Still, the relative weakness in consumer prices may lead PBOC Governor Yi Gang to feel pressure to add occasional bursts of monetary stimulus.

Nomura Holdings economist Lu Ting states that “after adjusting for base effects, we see a growing number of signs pointing to a weakening of post-Covid recovery momentum, especially in the real estate sector. We expect Beijing to step up policy support in the coming months.”

Yet rumors that China is sliding into a Japan-esque deflationary funk seem greatly exaggerated.

Similar:

Loading…