Global Courant 2023-04-15 14:00:28

The last time President Volodymyr Zelensky of Ukraine and China’s top leader Xi Jinping spoke, they celebrated 30 years of diplomatic ties. greet their “deepening political mutual trust” and the “intense friendship” of their people.

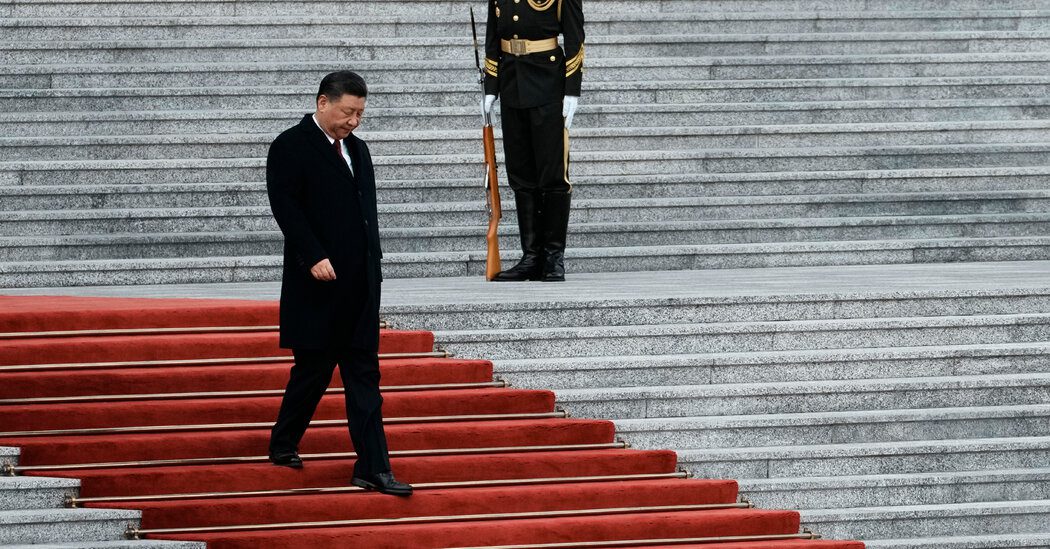

That was January last year. Less than two months later, Russia, one of China’s closest partners, invaded Ukraine. Mr. Xi has not spoken to Mr. Zelensky since then, despite his repeated requests. And the “healthy and stable” relationship they touted seems like a distant memory.

The question of whether and when Mr Xi will speak to Mr Zelensky – as Western leaders have also urged him to – reflects the precarious state of relations between their countries amid Russia’s war in Ukraine. Before the war, trade and cultural exchanges had grown. Now both parties are juggling goals that sometimes clash.

Ukraine is courting China for its potential to rein in Russian aggression. But it is well aware of Beijing’s demonstrated reluctance to do so, and of concerns that it could, in effect, arm Russia. Public opinion in Ukraine towards China is souring.

China, in turn, wants to maintain its professed neutrality in the conflict, and talks with Mr. Zelensky could bolster its desired image as a responsible global power. But it also portrayed the war as a proxy struggle over the future world order, with the United States on one side and itself and Russia on the other. Kiev’s embrace of the West puts it on the wrong side of that divide.

There is also the reality that Ukraine, as a country under attack, does not have the same economic appeal to China as before.

“Today’s Ukraine is still at war, Chinese investment there has been bombed, and we don’t know what Ukraine will look like in the future,” said Zhu Feng, a professor of international relations at Nanjing University. “Is there still a relationship between China and Ukraine?”

Before the invasion, the countries’ deeper ties were most apparent in their economic exchanges.

Between 2017 and 2021, Ukraine’s exports to China have quadrupled. In 2019, China was Ukraine’s largest trading partner and the largest importer of its barley and iron ore, This is according to a report by the Council on Foreign Relations. Ukraine was also China’s largest corn supplier and second largest arms supplier. China’s first aircraft carrier, the Liaoning, was a scrapped Soviet ship purchased in Ukraine and refurbished by the Chinese navy.

The then Prime Minister of Ukraine declared 2019 the ‘year of China’. Chinese companies were tapped for a new metro line in Kyiv. Ukraine’s free trade agreement with the European Union made it an attractive entry point for Chinese goods to flow into the lucrative market.

Cultural exchanges also grew. a statue in Beijing’s largest park honors a Ukrainian poet. Mr. Zelensky’s wife, Olena Zelenska, Delivered a virtual welcome to the 2021 Beijing International Film Festival. Many Ukrainians in China were students, This is reported by the Ukrainian embassy.

Yet geopolitical tensions always loomed. China refrain from criticism Russia after annexing Crimea from Ukraine in 2014. Ukraine has also been under pressure from the United States to distance itself from China, making it possible in 2021 scrap sales of $3.6 billion from a Ukrainian aerospace manufacturer to Chinese investors.

When Russian troops gathered at the Ukrainian border last year, Mr. Xi and President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia, meeting in Beijing, that their countries’ partnership has “no boundaries”.

After the start of the war, Beijing’s alignment became even more apparent. It adopted much of the Kremlin’s talking points and disinformation, accusing NATO of fomenting the conflict and refusing to call it an invasion. In the following year, Mr. Xi Mr. Met or spoken to Putin several times. On China’s heavily censored internet, popular videos celebrate Russian drone strikes, and nationalist influencers mock Ukraine’s turn to the West.

Still, Ukraine has tried to win China’s support, recognizing it as perhaps the only country with influence over Russia. Mr. Zelensky has done that repeatedly invoked China’s outspoken respect for territorial integrity.

While many of Ukraine’s allies have criticized what they consider China’s pro-Russian stance, Mr. Zelensky has been more cautious. He called Beijing’s recent position paper on the war, which many Western governments dismissed as lacking substance, “an important signal”. He has said that “I really want to believe” that China will not arm Russia.

But frustration with China has grown in Ukraine, in the government and among ordinary people, said Yurii Poita, who heads the Asia chapter of the Kiev-based New Geopolitics Research Network. An October poll a Ukrainian research group found that unfavorable views of China have doubled to 18 percent since 2021.

The visit of Mr. Xi to Moscow last month, where he and Mr. Putin reaffirmed their partnership is likely to have further dampened Kiev’s expectations.

“Ukraine had huge illusions about China for a long time,” said Mr. Poita. “But now I believe their illusion is gradually diminishing, especially after this visit.”

At the same time, China has toned down some of its rhetoric, especially as it tries to improve relations with Europe. Chinese officials have recently downplayed the significance of the “no borders” statement.

China may also see economic and strategic opportunities in rebuilding Ukraine, however the war ends, said Janka Oertel, director of the Asia program at the European Council on Foreign Relations. “This could be an attractive way to be part of a post-war reordering,” she said. “The Chinese government would like to keep that economic relationship as open as possible.”

Still, China will only go so far.

China’s foreign minister has spoken with his Ukrainian counterpart, but the government has declined to say more about whether top leaders will talk. Ursula von der Leyen, the head of the European Commission, said Mr Xi had told her last week that he was ready to speak with Mr Zelensky “when the circumstances and the time are right”.

Chinese experts argued that a phone call between the two would make little sense now that neither Ukraine nor Russia appear willing to agree to a ceasefire. even American officials have warned proposing a ceasefire for now, arguing that they would bolster Russian territorial gains.

“It’s not that we don’t connect, but the question is what would they talk about?” said Wang Yiwei, the director of the Institute of International Affairs at Renmin University in Beijing. He added to Mr Zelensky: “His hope of a call was that China would condemn the Russian invasion and call on Russia to withdraw its troops. That is not realistic.”

The uncertainty of the relationship trickles down to people like Anton Matusevych, a Ukrainian in Shanghai. Over eight years, Mr. Matusevych, 32, built a life there, opened a therapy business and married a Chinese woman.

He knows that many Chinese support Russia, but he has tried to build a community of people sympathetic to Ukraine by organizing cultural events and fundraisers. “You can’t change people’s opinions,” he said. But “we can try to find connections and build the future relationships.”

Yet his presence in China became increasingly conditional.

“We are trying to help, but at the same time we understand that this system is not helping Ukraine,” he said. If China armed Russia, he would leave: “There are lines we cannot cross.”

Marc Santora and Zixu Wang contributed reporting and research.