Global Courant 2023-04-20 12:19:20

Recent developments in the Middle East have made China a trusted intermediary and supporter of multilateral dialogue, indicating Beijing’s departure from Beijing’s typical reluctance to meaningfully engage in conflict negotiations.

Saudi Arabia’s and Iran’s decision to restore diplomatic relations has raised Beijing’s diplomatic profile and political clout. The agreement between the hostile powers in the Middle East, facilitated by China and other regional states, was followed by Saudi Arabia’s decision to become a dialogue member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, furthering the perception of China as a peacemaker .

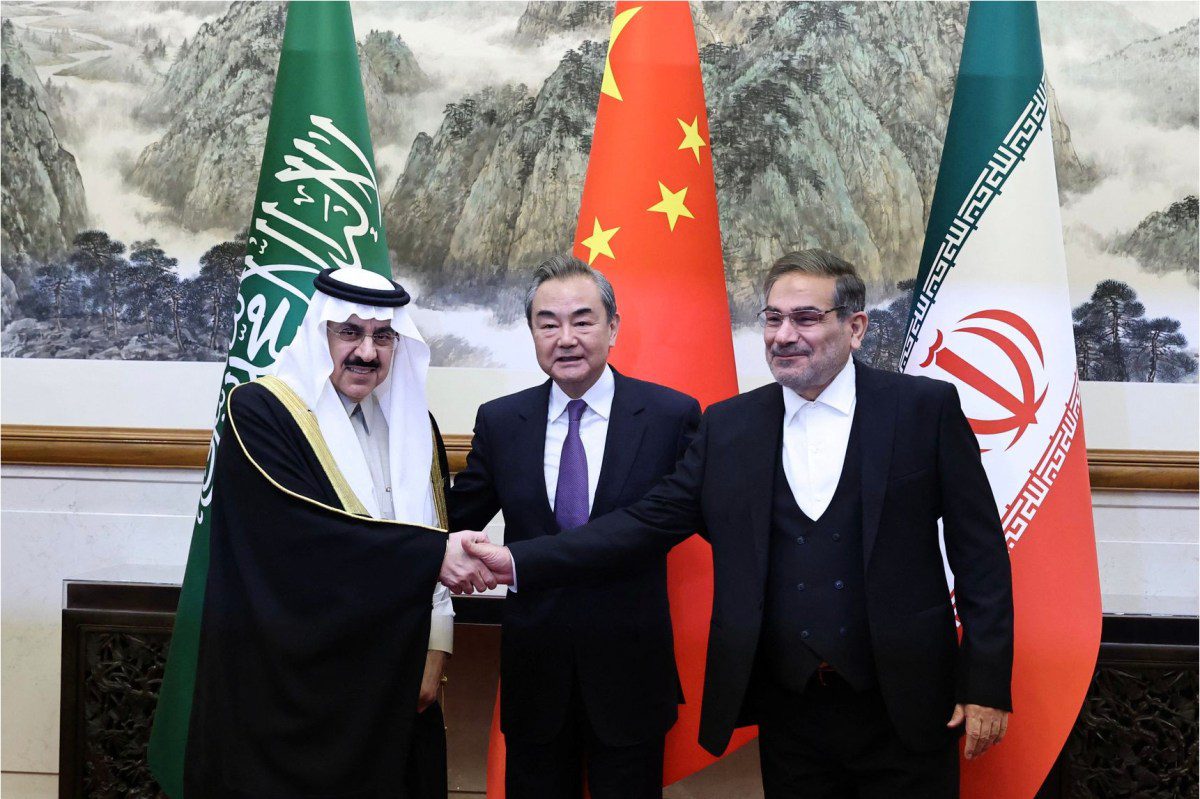

The initial agreement was followed by a meeting of Saudi and Iranian foreign ministers in Beijing on April 6, where the countries agreed to restore direct flights and deliberated on resuming government and private sector visits.

While detente may not lead to normalized relationships, China’s Diplomatic Victory signals its increasing willingness and ability to participate in conflict resolution and shape negotiation outcomes in its favor.

Beijing’s conflict management approach remains largely motivated by its economic interests and desire to project a favorable image. It is characterized by participation without deep involvement. But China is laying the groundwork for greater involvement and a values-based approach to conflict management.

Beyond Belt and Road

China’s role as a mediator has become prominent in the past decade. Beijing is more willing and able to influence the outcome of the negotiations.

Since the announcement of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013, Beijing’s involvement in conflict has grown beyond its traditional limited involvement approach. Before 2013, China rarely participated in international mediation initiatives, preferring to be a neutral spectator and remain flexible.

Beijing’s recent diplomatic involvement in the Middle East, Afghanistan, Myanmar and Ethiopia shows Beijing’s intention to play a more political and diplomatic role in conflict zones. Yet China’s quasi-mediation approach, in which it mainly defends its commercial and political interests, is driven by economic interests and international image.

China’s interests in the Middle East, Africa and Asia in the form of the BRI and other trade and energy flows encourage Beijing to take a more active part in shaping the outcome of major diplomatic negotiations.

Take China’s participation in the rapprochement between Saudi Iran, where energy imports are significant. In 2021, Saudi Arabia delivered China with 18% of its crude oil needs. Beijing is Saudi Arabia’s largest buyer of oil. Interdependence in Saudi-China relations encouraged China to participate as an influential mediator.

Similarly, China is Iran’s main economy partner, forcing Tehran to meaningfully engage in diplomatic negotiations with Saudi Arabia. China’s excessive economic clout in both countries gives it leverage to regulate their political behavior through quasi-mediation.

View the long term

China’s lack of historical baggage in the Middle East has also given it the image of a neutral mediator. Beijing’s BRI enterprises, energy dependency and trade relations also keep it invested in the long run. Securing a stable Middle East is in China’s interest, just as maintaining a stable relationship with Beijing is in the interest of Riyadh and Tehran.

Image-driven considerations also determine China’s participation in conflicts, as evidenced by the peace proposals in Ukraine. China’s peace plan in Ukraine has less to do with ending the war and more with cultivating the peacemaker image. The plan presented China as a neutral mediator, a position that is very popular with developing countries.

French President Emmanuel Macron highlighted China’s potential role as a peacemaker in the conflict and urged President Xi Jinping to “bring everyone back to the negotiating table”. This underscores the growing perception that Beijing’s involvement in conflict mediation is necessary to reach meaningful solutions.

While China’s attempts to mediate in the Middle East between the Taliban and the government of Afghanistan and in South Asia between Bangladesh and Burma reaffirming its stance as a mediator and providing a contrast to US-led conflict mediation efforts.

Beijing has also expanded its diplomatic involvement in Africa, particularly in Ethiopia – a central hub in the BRI. Beijing has offered mediate disputes at a time when the United States’ relationship with warring factions in the region continues to deteriorate.

China’s mediation continues to follow a policy of limited engagement, choosing to participate in the dialogue without using its position to achieve meaningful results. While this fits with Beijing’s desire to project a benign image, the mediation policy of the past decade indicates a gradual change in China’s attitude towards more active political involvement in conflict.

Beijing’s ability to mediate conflict is largely determined by its lack of historical baggage, its decision to remain neutral and its ability to provide economic incentives to warring states. China is eager to use its perception of neutrality to become more politically involved in future conflicts.

While China’s involvement in conflicts is still determined by interests, China is poised to develop a values-based approach to dispute resolution. The Global Security Initiative (GSI) is the most visible effort to create an alternative security architecture that sets standards for conflict resolution in developing countries.

China already has it mention that the Iran-Saudi rapprochement is an example of the GSI in action.

China’s intention to take a more active and engaged role in mediating conflicts should force the United States and other regional powers to take a more constructive role in conflict areas. Allowing China to shape the outcome of conflicts allows Beijing to expand its interests and influence at the expense of other states such as the US, India and Japan.

This article was first published by East Asia Forum, which is based on the Crawford School of Public Policy within the College of Asia and the Pacific at the Australian National University. It has been republished under a Creative Commons license.

Similar:

Loading…