Global Courant

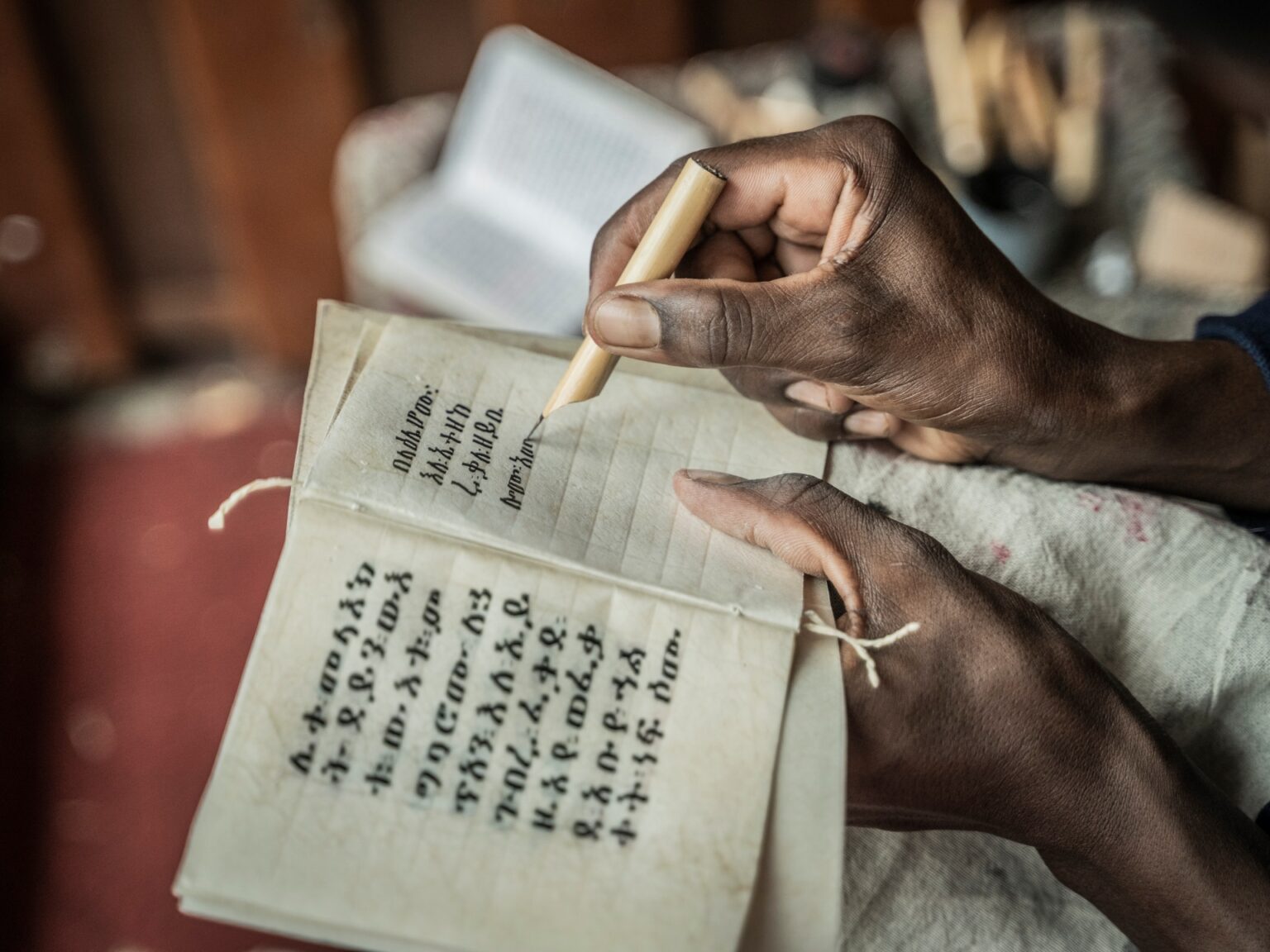

Armed with a bamboo-ink pen and a steady hand, Ethiopian Orthodox priest Zelalem Mola carefully copied text in the ancient Ge’ez language from a religious book on goatskin parchment.

This painstaking task preserves an old tradition while also bringing him closer to God, the 42-year-old said.

At the Hamere Berhan Institute in Addis Ababa, priests and lay worshipers work by hand to replicate sometimes centuries-old religious manuscripts and sacred works of art.

The parchment, pens and ink are made in the institute, located in the Piasa district in the historic heart of the Ethiopian capital.

Yeshiemebet Sisay, 29, who is responsible for communications at Hamere Berhan, said the work started four years ago.

“Old parchment manuscripts are disappearing from our culture, which is what motivated us to start this project,” she said.

The precious works are mainly kept in monasteries, where prayers or religious chants are performed using only parchments instead of paper manuscripts.

“This habit is fading fast. … We thought that if we could learn skills from our priests, we could work on them ourselves, so that’s how we started,” Yeshiemebet said.

‘It’s hard work’

In the institute’s courtyard, workers stretch goatskins taut over metal frames to dry under a faint sun.

“After the goatskin has been submerged in the water for three to four days, we make holes in the edge of the sheet and bond it to the metal so it can stretch,” said Tinsaye Chere Ayele.

“Then we remove the extra layer of fat on the inside of the skin to clean it.”

With two other colleagues, the 20-year-old performed his task using a makeshift scraper, seemingly oblivious to the stench emanating from the animal hide.

Once clean and dry, the hides are stripped of their goat hair and then cut to the desired size for use as book pages or for painting.

Yeshiemebet said most of the manuscripts are commissioned by individuals, who then donate them to churches or monasteries.

Some clients order small collections of prayers or paintings for themselves to have “reproductions of ancient Ethiopian works,” she said.

“Small books can take one or two months. If it is a collective work, large books can take one to two years.

“If it’s an individual task, it can take even longer,” she said, flipping through books wrapped in red leather, the texts of which were decorated with brightly colored illuminations and religious images.

Sitting in one of the institute’s rooms with parchment pages on his knees, Zelalem patiently copied a book entitled Zena Selassie (History of the Trinity).

“It’s going to take a lot of time,” said the pastor. “It is hard work, starting with the preparation of the parchment and the inks. This can take up to six months.”

“We make a bamboo stylus and sharpen the tip with a razor blade.”

The scribes use different pens for each color used in the text – black or red – and a fine or broad nib. The inks are made from local plants.

“Talking to Saints and God”

Like most other religious works, Zena Selassie is written in Ge’ez.

This dead language remains the liturgical language of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, and its alpha-syllabic system—in which the characters represent syllables—is still used to write Ethiopia’s national language, Amharic, as well as Tigrinya, which is called spoken in Tigray and neighboring Eritrea.

“We copy from paper to parchment to preserve (the writings) as the paper book is easily damaged, while this book will last a long time if we protect it from water and fire,” Zelalem said.

Replicating the manuscripts “needs patience and focus. It starts with prayer in the morning, at lunch and ends with prayer.”

“It’s hard for an individual to write and finish a book just to sit around all day, but thanks to our dedication, a light shines within us,” Zelalem added.

“It takes so much effort that it makes us worthy in the eyes of God.”

This spiritual dimension also guides Lidetu Tasew, who is responsible for education and training at the institute, where he teaches painting and enlightenment.

“Spending time here painting saints is like talking to saints and to God,” said the 26-year-old.

“We have been taught that wherever we paint saints is the spirit of God.”

(TagsToTranslate)Features