Global Courant 2023-04-26 09:06:48

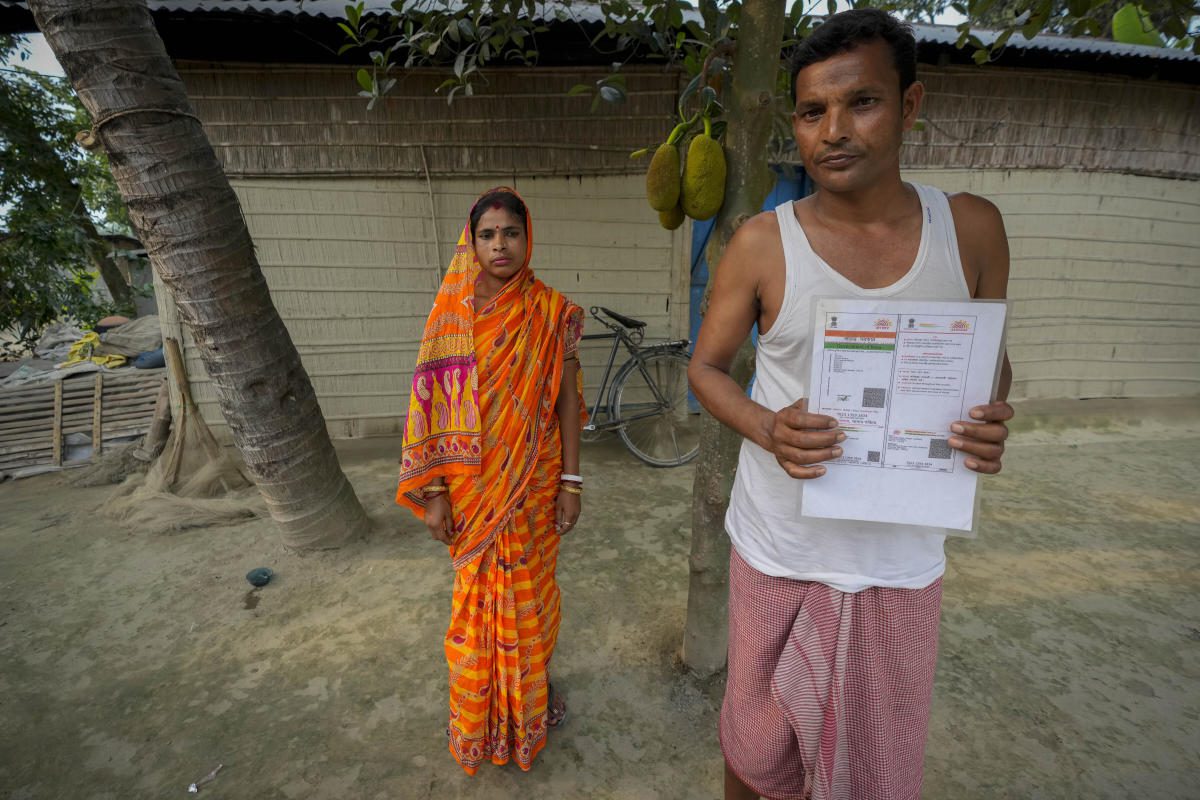

MURKATA, India (AP) — Krishna Biswas is scared. Unable to prove his Indian citizenship, he risks being sent to a detention center far away from his modest bamboo-timbered hut that overlooks fields lush with maize.

Biswas says he was born in India’s northeastern state of Assam. Just like his father, almost 65 years ago. But the government says that to prove he is an Indian, he must provide documents dating back to 1971.

For the 37-year-old vegetable seller, that means looking for a decades-old title deed or a birth certificate with an ancestor’s name on it.

Biswas doesn’t have one and he’s not alone. There are nearly 2 million people like him – more than 5% of Assam’s population – staring at a future where they could be stripped of their citizenship if they fail to prove they are Indian.

Questions about who is an Indian have long lingered in Assam, which many say is overrun with immigrants from neighboring Bangladesh.

At a time when India is poised to overtake China as the most populous countrythese concerns are expected to grow as Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government tries to leverage illegal immigration and the fear of demographic shifts for electoral gain in a country where nationalist sentiments run deep.

The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party has pledged to roll out a similar citizenship verification program across the country, even as the process in Assam has been suspended after a federal audit found it flawed and riddled with errors.

Nevertheless, hundreds of suspected immigrants with voting rights in Assam have been arrested and sent to detention centers that the government calls ‘transit camps’. Thousands have fled to other Indian states for fear of arrest. Some have died of suicide.

___

EDITOR’S NOTE: This story is part of an ongoing series exploring what it means for India’s 1.4 billion people to live in what will become the world’s most populous country.

___

Millions of people like Biswas, whose citizenship status is unclear, were born in India to parents who emigrated many decades ago. Many of them have voting cards and other means of identification, but the state’s citizenship register only counts those who can prove, with documented evidence, that they or their ancestors were Indian citizens before 1971, the year Bangladesh was born.

Story continues

Modi’s party, which also rules Assam, says the register is essential to identify people who have entered the country illegally in a state where ethnic passions are deep-rooted and anti-immigrant protests culminated in the massacre of more than 2,000 Muslim immigrants in the 1980s.

“My father and his brother were born here. We were born here. Our children were also born here. We will die here, but not leave this place,” Biswas said on a recent afternoon at his home in Murkata village in Assam, near the banks of the Brahmaputra River.

The Biswas family has 11 members, nine of whom have their citizenship disputes. His wife and mother have been declared Indian by an aliens tribunal that decides on applications for citizenship. Others, including his three children, his father and his brother’s family, have been declared “foreigners”.

It makes no sense to Biswas, who wonders why some are considered to have settled in the country illegally and others are not, even though they were all born in the same place.

The family, like many others, has not taken their case to the tribunal or higher courts due to lack of funds and the tedious paperwork involved.

“If we can’t be Indian, just kill us. Let them (the government) kill my entire family,” he said.

The registry was last updated in 2019 and excluded both Hindus and Muslims, but most critics view it as an attempt to deport millions of Muslim minorities.

They say the process would become even more exclusive if Modi’s party revives a controversial citizenship law that grants citizenship to persecuted believers who entered India illegally from neighboring countries, including Hindus, Sikhs and Christians, but not Muslims. The nationwide citizenship law was introduced in 2019, but sparked widespread protests across India over Muslims being singled out, forcing the government to put it on the back burner.

Supporters of the register say it is essential to protect the cultural identity of the indigenous people of Assam, arguing that those who have entered illegally are taking their jobs and their land.

“The influx of illegal foreigners from Bangladesh threatens the identity of the indigenous people of Assam. We cannot remain as a second-class citizen among illegal Bangladeshis. It is a matter of our own existence,” says Samujjal Bhattacharya, who was part of a movement in Assam against illegal immigration.

Dozens of people in Assam have committed suicide in fear of possible loss of citizenship, leaving a trail of destruction among families.

When Faizul Ali was sent to a detention center in late 2015 after being declared a “foreigner”, his relatives feared they would be next. The prospect of being thrown in jail drove his son to commit suicide. His brother tried to save him, but drowned in the process. A year later, Ali’s other son hanged himself.

Ali was released on bail from the detention center in 2019. He died in March, leaving behind his wife, a mentally ill son, two daughters-in-law and their children. They all live in a one-room house made of corrugated cardboard in the Muslim village of Bahari. They have all been declared “foreigners”.

Ali’s wife, Sabur Bano, can’t make ends meet and has turned to begging. She cannot afford firewood for cooking and uses discarded clothing she collects on the street as fuel.

“I am a citizen of this country. I am 60 years old. I was born here, my children grew up here, all my possessions are here. But they made me a foreigner in my own country,’ she said, wiping tears from the hem of her white sari.

Others are still waiting for their loved ones after being arrested.

On a recent morning, Asiya Khatoon boarded a rickshaw and traveled nearly 31 kilometers (19 miles) from her home to a detention center in the city of Assam, where her husband has been held since January.

“They (police) just came to pick up my husband and said he is Bangladeshi,” said the 45-year-old, before hurriedly walking to the detention center surrounded by a huge perimeter of walls and watchtowers with security cameras and armed guards.

In her hands she held a crumpled plastic bag. It was wearing a green T-shirt, pants and a cap that she wanted to give to her husband.