Global Courant 2023-05-11 15:36:38

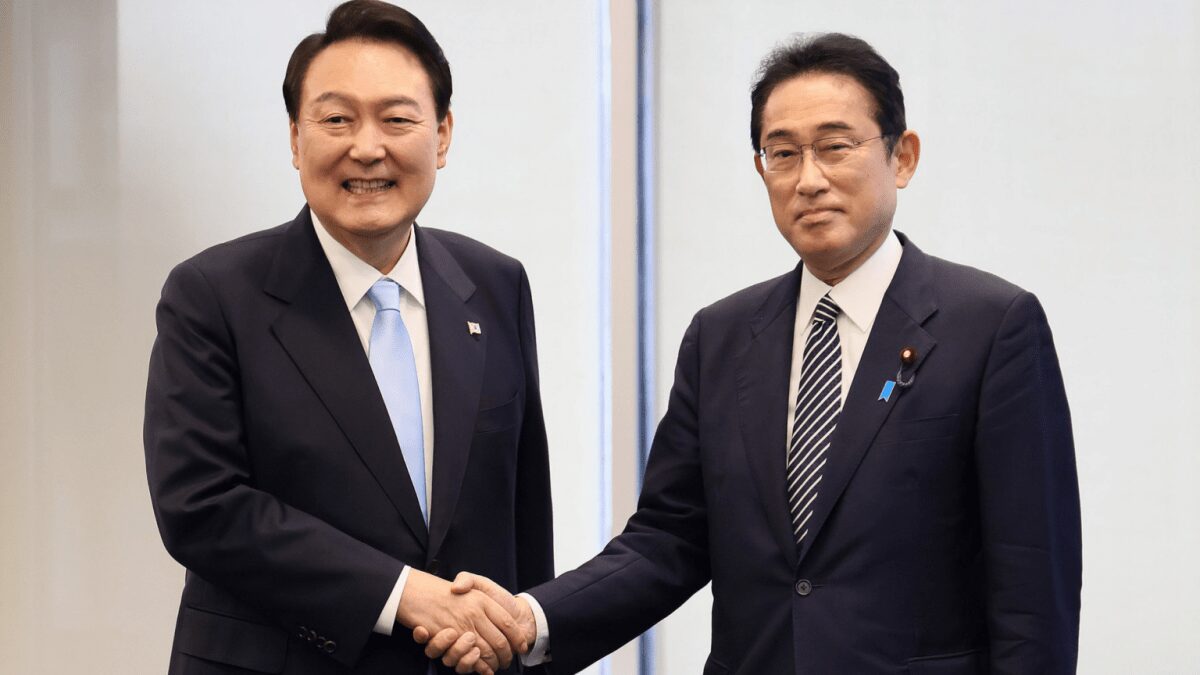

Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s visit to Seoul on May 7-8, 2023 represents a triumph of geopolitics in the quest for historic justice. Both South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol and Kishida are now driven by the ominous international environment, led by threats to international order from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and China.

Kishida remained cautious in responding to South Korean calls for apology and compensation for the victims of Japan’s wartime colonial and forced labor system. These problems were exacerbated by later trade and security tensions.

But he acted urgently to restore relations between South Korea and Japan to normal and sharpen cooperation on a wide range of shared concerns. These concerns ranged from regional security in the face of North Korean missile and nuclear advances to supply chain resilience and controlling the flow of advanced electronic technology to China.

Both Japan and South Korea are embracing the strategic direction coming from Washington. They understand that their survival, both nationally and politically, depends on to subordinate oneself to the global and regional priorities of US President Joe Biden.

“Korea cannot strengthen its alliance with the United States unless Korea maintains a good working relationship with Japan, and Yoon knows that very well,” former foreign minister Yu Myung-hwan, an adviser to Yoon, told me.

He added that “Chinese bullying may also have been a motivation to restore trilateral security cooperation” and that “increasing North Korean nuclear threats are a good excuse for him to strengthen trilateral security cooperation.”

The compressed diplomatic calendar of early 2023 reflects the determination of both leaders – and their American backers – to bring about the dramatic shift in relations. The shift in relations between South Korea and Japan began in early March 2023 Yoon’s decision to end the stalled negotiations on the issue of forced labour.

South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol has made a clear choice for the New Cold War. Image: CNN/Screengrab

Instead, Yoon used a South Korean fund to unilaterally offer compensation to survivors and their families who went to court, scrapping demands for apologies and payments from Japanese companies. Within days of his decision, Yoon visited Tokyo and important steps were taken to return to a corporate atmosphere.

The trip to Tokyo was necessary for that Yoon’s state visit to Washington in April 2023. A diplomatic showcase of the alliance is embodied in a “Washington Declaration” that strengthened expanded deterrence in exchange for South Korea’s renunciation of nuclear ambitions.

There are indications that the Biden administration now wants to establish a trilateral comprehensive deterrence dialogue. Yoon told reporters Japan could be added to the Nuclear Consultative Group established under the Washington Declaration, but his office weakened that wording as it would undermine his performance with South Korea.

Still, a trilateral security dialogue between Japan, South Korea and the United States would provide a formidable response to both North Korea and China, and even a potential Sino-Russian military axis. It would also lead to a trilateral meeting in June between defense ministers, which would reportedly formalize the sharing of missile defense data – a target set for 2023.

Both Yoon and Kishida made ample reference to geopolitical goals during their only public appearance together at a joint press conference. “We are the US’s main allies in Northeast Asia”, Kishida said. He also stressed that Japan and South Korea are seeking to strengthen their deterrence and response capabilities against North Korea through a series of security alliances between Japan, South Korea and the United States.

Still, unresolved issues of historical justice could not simply be brushed aside. Leading up to the visit, progressive and conservative South Korean media expressed expectations that Kishida would go further than previous statements and issue a personal apology – perhaps opening the door for Japanese corporate payments to victims.

Kishida, under pressure from vocal conservatives who opposed any further Japanese apology or admission of responsibility for repression in South Korea, was hesitant to go that far. But he decided to express his personal sympathy for the victims by telling reporters his “heartache” over their suffering.

He also provided South Korea with access to the Fukushima nuclear site to allay concerns about radioactive contamination in released waters. According to Japanese mediaKishida wanted to make some concessions to support Yoon against criticism in South Korea of his eagerness to give in to Japan without much in return.

The shadow of the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster has long hung over Japan’s nuclear energy sector and relations with Korea. Photo: AFP/TEPCO/JIJI Press

The gestures met with a divided response in South Korea – progressive politicians and media were dismissive, and while conservative supporters of Yoon appreciated Kishida’s apparent sincerity, they were not overwhelmed.

Former Foreign Minister Yu said that “Kishida failed to directly apologize to the Korean people and clearly lacked the political courage to do so,” but that President Yoon “believes it is not politically correct to beg the other party to apologize.”

This leaves historical issues still buried like land mines, not far from the surface and ready to go. More court hearings on victims of forced labor in a separate lawsuit against Mitsubishi Heavy Industries set to commence May 11, 2023.

For now, geopolitical imperatives will maintain the momentum created in early 2023.

Daniel Sneider is a lecturer in international policy and East Asian studies at Stanford University and a nonresident Distinguished Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute.

This article was originally published by East Asia Forum and has been republished under a Creative Commons license.

Similar:

Loading…