Global Courant 2023-05-01 17:30:22

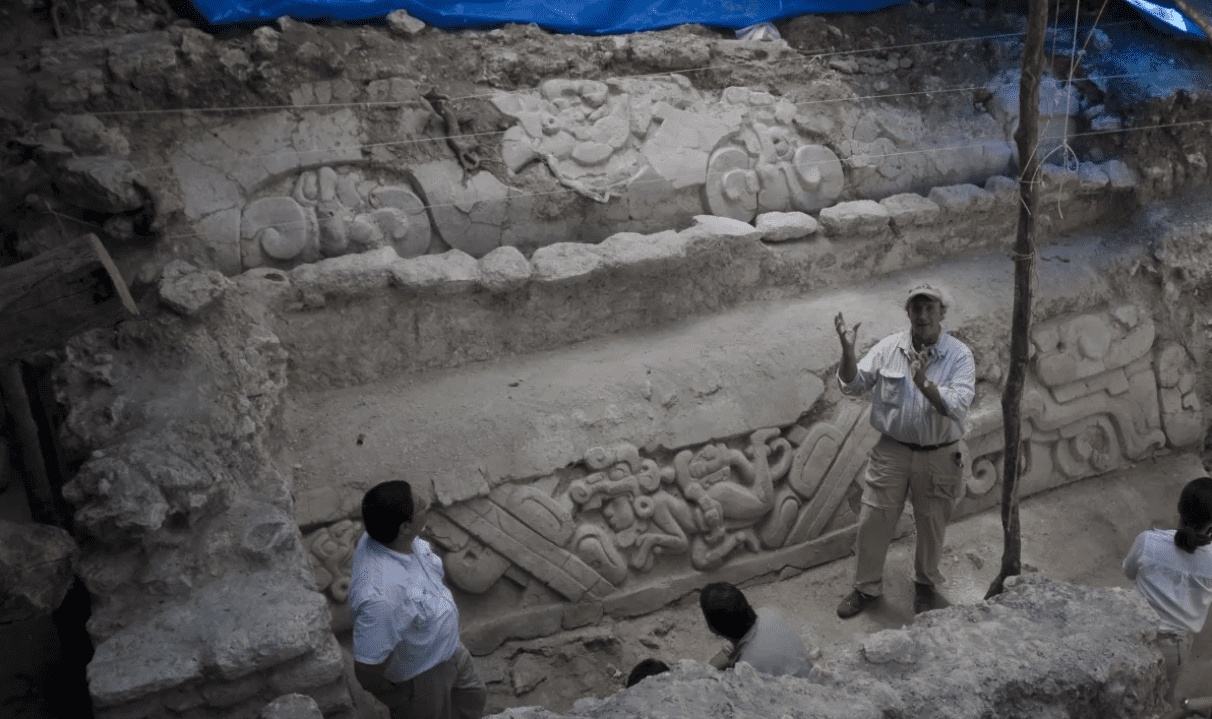

A little over a year ago, I joined archaeologist Richard Hansen on one of his frequent expeditions to the El Mirador region, in Guatemala’s Petén jungle bordering Mexico, which Hansen believes was the cradle of ancient Maya civilization. It was a fascinating, sometimes terrifying journey and last December I went with him for the second time.

On those occasions, I learned how, using LiDAR technology, Hansen and his research team had discovered more than 964 archaeological sites and found 417 towns connected by a complex network of roads. But today the sites threaten to be overrun by illegal activities: poaching, logging, and drug and human trafficking.

His team’s concern, Hansen told me, “is how to protect El Mirador without it falling into the hands of the big interests that roam the area, and we believe the best way to do this is to make it a bi-national nature reserve. .”

Last weekend, Hansen came from Guatemala to participate in the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books on the USC campus. I had invited Hansen to talk to me about his research so that Angelenos, including our local Mayan community, could learn more about his research, including the lessons he believes the possible fate of the ancient Maya for our warming planet has in store.

“The fate of that archaeological zone is tied to the protection of the forest,” Hansen said.

But on April 23, when we had been talking for barely three minutes, a local group of masked protesters claiming to be members of the Mayan community rushed onto the stage, grabbed our microphones, threw chairs, knocked over the speakers and smashed one of the stage crew.

Hansen’s message was drowned out by the protesters, who shouted at Hansen as they unveiled a banner that read: “Gringo colonizer fuera del Mirador.” The protesters accuse Hansen of appropriating the cultural heritage of the Guatemalan people for personal benefit by turning the impoverished region into an archaeological theme park.

“There’s nothing false about that,” Hansen told me as we waited behind a wall of police officers who quickly arrived to protect us from the protesters. “My proposal is the exact opposite of what these people are saying.”

When I went to El Mirador with Hansen and his team last December, I asked him about previous similar accusations from his detractors that he wants to turn the Maya complex into a tourist Disneyland. He laughed out loud.

“They misrepresented everything,” Hansen told me. On the contrary, Hansen fears that major capital investment in the region “should be avoided at all costs”. Not only would it get in the way of his own work, but he is convinced that an invasion of new highways, airports, hotels and recreation areas would destroy the surrounding jungle.

Hansen, on the other hand, said he proposes creating an environmentally sustainable refuge that would generate jobs for the local indigenous communities and lessen the influence of the “mafia” who are destroying the area.

According to Hansen’s research, the El Mirador-Calakmul Basin has an extension of 3,500 square kilometers (about 1,350 square miles) in Guatemala and a similar extension in Mexico’s Campeche state and currently the only way to access the archaeological sites by helicopter from Las Flores, or nearly three days’ walk from the municipality of Carmelita.

“To reduce environmental impact, we proposed building a light rail, like the one at Disneyland, that would provide access for tourists with minimal environmental impact,” Hansen said. “We also proposed that the communities themselves should be in charge of not only light rail, but all the infrastructure needed to serve tourists.”

That proposal – which was nothing more than a proposal – has earned him many enemies and led to verbal attacks and even some death threats.

“There are a lot of interests that have their eye on that area, and they don’t want the area to be protected,” he told me.

I specifically asked who threatened to kill him. “I’d rather not say,” he replied, “but there have been specific death threats against me and my family in 2001 and in 2020.”

I have traveled through the El Mirador area twice and the lack of surveillance by the Guatemalan government is notorious. There are only a handful of armed guards who are paid by the Guatemalan government to patrol the vast area.

On my last trip, one of the government guards who asked not to be identified told me that he and his colleagues regularly see planes unloading drugs in the area, but there’s nothing they can do. “We have no weapons and no authority to intervene,” he told me. Hansen’s archaeological team is keeping a group of 16 guards in the area to try to protect the site and lessen the impact of illegal activity.

Hansen also believes that the jungle’s natural resources can be sustainably developed for the benefit of local communities without having to decimate the forest. Estuardo Labbé, director of the Guatemalan Foundation for Anthropological Research and Environmental Studies (FARES), told me that in order to preserve the forest, FARES even offered to buy trees from the logging companies operating in the area. But those offers were rejected.

“They didn’t want to, despite the fact that there is a large market for natural products from the forest in Europe and the United States,” says Labbé.

Last weekend, news of the Los Angeles demonstration spread quickly through social media. Among the commentators was Italian Guatemalan archaeologist Francisco Estrada-Belli, who had long been critical of Hansen’s work. He tweeted, apparently referring to the protests: “That happens when you try to undermine the conservation of forests and livelihoods of local communities in #Peten, #Guatemala by introducing a bill in the US Senate (S.3131) to make you fund plan. through the back door.”

The U.S. Senate bill that Estrada-Belli was referring to was the “Mirador-Calakmul Basin Maya Security and Conservation Partnership Act of 2019,” sponsored by Senator James M. Inhofe (R-Okla.). Its stated goal was “to promote collaborative research efforts between the United States and local entities to create a sustainable tourism model that provides controlled, low-impact access to the archaeological sites of the Mirador-Calakmul Basin in Central America, with the emphasis on providing economic opportunities for communities in and around the watershed.”

Hansen told me, “There was nothing hidden or under the table during that negotiation.”

“When we spoke to members of the United States Senate, it was 13 Guatemalan representatives and the culture minister of President Jimmy Morales’ administration,” he said.

The bill, if passed, would have allocated $144 million that could have been used by public or private entities to fund infrastructure projects to help preserve the jungle and support scientific research. To access these funds, each entity would have to go through an open and transparent bidding process.

“It’s a real tragedy that it wasn’t adopted because it would have benefited thousands of people living in very poor communities without work,” Hansen said.

Among those who support Hansen’s proposals are some of the people most directly affected by them: members of the various Mayan communities in Central America and the United States. Centuries after the Spanish settlers arrived in the Western Hemisphere, the Maya continue to struggle against poverty, discrimination and ruthless oppression. They were the main target of the civil war that devastated Guatemala between 1960 and 1996, in which hundreds of thousands of indigenous peoples died.

A day before the incident at the book festival, Hansen and archaeologists Enrique Hernández, an expert on El Mirador, and Beatriz Balcarcel, an expert on the Acropolis, met with a group of about 300 people of Mayan descent in Los Angeles. to publicize their proposals.

Edgar Leonel Chaj, vice president of Maya Visión and secretary of the Los Angeles Mayan Cultural Committee, told me, “We had doubts and we wanted to hear from Hansen himself the details of what he’s proposing and we agreed with him that it’s as the Mayan peoples who have to decide how to protect that area and how to benefit from that cultural legacy.”

Chaj lamented the acts of violence by the demonstrators, who he said were not informed or paid by anyone, so Hansen could not deliver his message. “They probably didn’t want his message about creating a sanctuary to get out.”

I also spoke with Nesha Xuncax, secretary of Maya Visión, who also attended Hansen’s talk with the Maya leaders.

“We openly asked Hansen if there was a hidden agenda in his El Mirador development proposals, and of course he didn’t answer that, and I believe him, because he has made every one of his proposals public,” Xuncax said.

She added that there are many hidden interests in the Petén region. “Corrupt governments, the ones that keep the Guatemalan people in poverty, are the ones that have aligned themselves with those interests,” she continued. “In any case, Hansen’s proposal takes into account the Maya and their needs. It would be absurd not to support it.”

According to her, a disinformation campaign is underway against Hansen, designed to discredit him and prevent the El Mirador area from being protected.

Meanwhile, Hansen told me that another group, the Mayan Cultural and Natural Heritage Foundation (Pacunam) “has already presented concrete investment projects.”

“There is already a proposal to build highways, gas stations, hotel chains, restaurants and airports on a large scale,” he said. “Actually, they accuse me of what the big investors want to do. Unfortunately, the protestors in Los Angeles are apparently unaware of these projects and are once again lending themselves to the exploitation of the Mayan people.”