Global Courant 2023-05-07 09:04:35

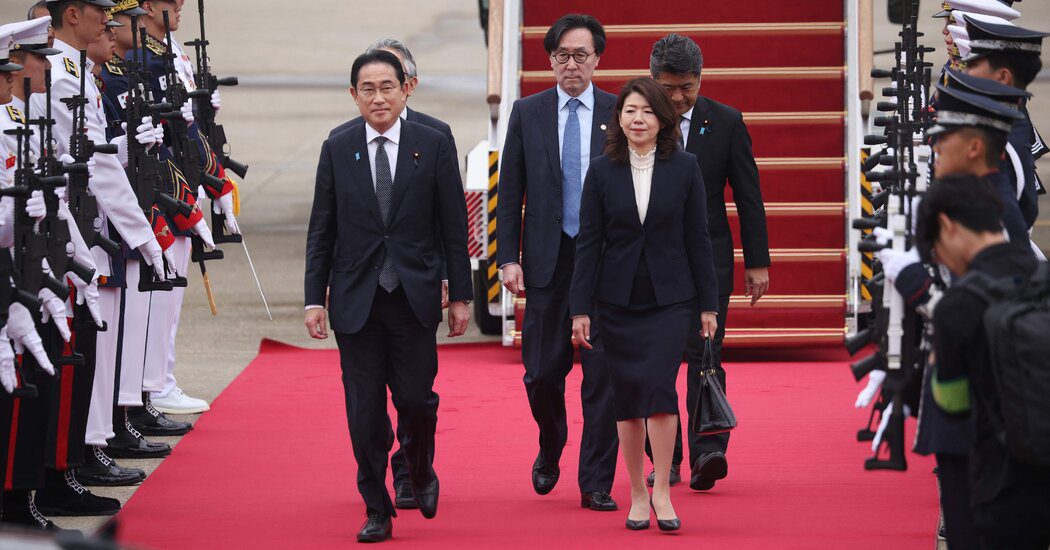

When Prime Minister Fumio Kishida of Japan arrived in Seoul on Sunday to foster a fledgling détente between neighboring countries, South Koreans anxiously awaited what he had to say about Japan’s ruthless colonial rule over the Korean Peninsula in its early days of the 20th century.

Mr. Kishida’s two-day trip follows a March visit by South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol to Tokyo. It means shuttle diplomacy between two key US allies is back on track after regular exchanges between the countries’ leaders were abruptly ended in 2011 over historic disagreements.

Few countries are as happy with the thaw as the United States. For years, it has urged Tokyo and Seoul to let go of past grievances and step up their cooperation, both to deter North Korea’s nuclear threat and to help Washington curb China’s economic and military ambitions. to hold.

Meeting with Mr. Yoon in Washington late last month, President Biden thanked the South Korean leader for his “courageous, principled diplomacy with Japan”.

In March, Mr. Yoon hit a roadblock in relations with Japan when he announced that South Korea would no longer demand Japanese compensation for victims of forced labor during World War II, but would create its own fund for them. Mr Yoon said that Japan should no longer be expected to “kneel because of our history of 100 years ago”.

The olive branch to Tokyo is part of Mr Yoon’s wider effort to reshape South Korean diplomacy, bringing his country closer to countries with “shared values”, especially the United States, on issues such as supply chains and a ‘free and open’ Indo-Pacific.

Mr. Yoon’s diplomatic concessions were a political blessing for Mr. Kishida at home only precious to Mr. Yoon in his own country, where South Koreans accused him of “treacherous, humiliating diplomacy”. His domestic critics say he gave too much and received too little in return from Japan, which they say has never apologized or reconciled — a common complaint from many other Asian victims, especially in China and North Korea, of Japan’s aggression during the Second World War.

For many South Koreans, the most important thing about relations with Tokyo is how Japanese leaders view the colonial era, a time when Koreans were forced to adopt Japanese names; when schools removed Korean language and history from the curriculum; and when tens of thousands of Korean women were forced into sexual slavery for the Imperial Japanese Army. They’ll likely judge Mr. Kishida’s visit by whether — and how directly — he’ll apologize for that past.

“South Koreans are all ears for what Kishida will say about history,” said Lee Junghwan, an expert in Korea-Japan relations at Seoul National University. “If he says something vague, just making wordy references to past statements by Japan’s leaders, as he probably will, it won’t go down very well.”

Mr. Yoon’s government has tried to sell South Koreans during his outreach by raising hopes that Japan would give back, for example by allowing Japanese companies that benefited from wartime forced labor to make voluntary contributions to the South Korean Victims Fund. In recent weeks, Tokyo lifted export controls imposed on South Korea after the forced labor dispute broke out in 2018 and began the process of putting the country back on its “white list” of preferential trading partners.

But if Mr. Kishida fails to live up to South Koreans’ expectations of history, “it will cast a shadow over everything they’ve accomplished in recent months,” said Daniel Sneider, a professor of East Asian studies at Stanford University. university. “It is more important what he says about the past than whether, say, Japanese companies ultimately contribute to the fund for the Korean forced laborers.”

The trip to Seoul is a test of leadership for Mr. Kishida, and an opportunity to show he can expand Mr. Yoon’s efforts for reconciliation, analysts said.

“There is an unusual opportunity for him to display bold statesmanship and shift the seemingly endless vortex of negativity between Japan and Korea,” said University of Connecticut Prof. Alexis Dudden, an expert on relations between Korea and Japan.

For example, Mr Kishida could make a reflective visit to each of Seoul’s monuments to the suffering Koreans endured under the Japanese occupation, Professor Dudden said, comparing such a move to a 1970 visit to Poland by German Chancellor Willy Brandt. But doing so – let alone kneeling before a monument, as Chancellor Brandt famously did in Warsaw – may be asking too much of Mr. Kishida, given that his country’s right-wing nationalists are on the verge of “letting him pay for everything they describe as being weak to Korea in the mud-throwing memory wars between the countries,” she said.

The last time a Japanese leader visited South Korea, relations were so bad that the prime minister, Shinzo Abe, emphatically remained seated during a standing ovation as North and South Korean Olympians marched together during the opening ceremony of the Pyeongchang Olympics in 2018.

Mr Kishida, who traveled in a more amicable mood, has said he wanted to “give a boost” to improving relations. But few analysts believed that decades-long tensions will easily dissipate given the political pressures at home for both leaders.

“More than 90 percent of our bilateral relationship is domestic politics,” said Kunihiko Miyake, a former Japanese diplomat. “So South Koreans cannot pardon us. They will continue to pressure us and want to keep this kind of relationship forever by moving the goalposts.”

For his part, Mr. Kishida needed the support of right-wing politicians in Japan, who are among the most influential in selecting party leaders. Mr Miyake said he would be “surprised” if Mr Kishida “suddenly makes overly conciliatory remarks towards South Korea.”

Still, Tokyo may be considering how to deal with subtle pressure from the United States, analysts said.

Biden’s repeated praise for Mr. Yoon’s diplomacy was “kind of a message not only to President Yoon but also to Kishida,” said Junya Nishino, a law professor at Keio University in Tokyo. Mr Nishino added that recent electoral victories by Mr Kishida’s party in special elections last month could also give him “more diplomatic space”.

Mr. Yoon’s own determination to improve ties with Tokyo is supported in part by changing public opinion in South Korea. In recent surveys, China has replaced Japan as the country rated least favorably, especially by younger people.

But doubts about Japan have deeper roots among South Koreans than Mr. Yoon might like to believe, analysts say. A survey conducted in March found that 64 percent of South Korean respondents said there was no reason to hurry to improve ties unless Japan changed its attitude to history.

Ms. Dudden warned Seoul, Tokyo and Washington not to “treat history as mere background music to the present and irrelevant to how it informs immediate concerns — in this case, steadfast to North Korea and increasingly to China as well.”

As the history of bilateral ties between South Korea and Japan has repeatedly shown, a conciliatory move over a historic dispute accomplishes little if another dispute, such as over the territorial rights over a series of islands between the two nations, is reignited.

“The history issues have a way of coming back and biting you in the back,” Mr Sneider said. “These are not just short-term public opinion issues. They are issues of identity in Korea.”