Global Courant 2023-05-31 13:25:37

JAKARTA – The recent death of the sole survivor of the sinking of the Australian light cruiser HMAS Perth in the Sunda Strait in World War II has drawn attention to hundreds of warshipwrecks and the remains of their crewmen lying on the bottom of the Southeast Asian seas lie. .

After years of effort, it was only in 2018 that the Australian and Indonesian governments agreed to declare the area around 7,100-ton Perth and the nearby wreck of the US cruiser USS Houston a maritime memorial park.

It was almost too late. Archaeologists from the Australian Maritime Museum found that between 2015 and 2016 about 60% of the Perth’s starboard plating was removed in an industrial-scale operation that disturbed the graves of the 357 Australian sailors in the process.

Salvage ships reportedly looted as many as 40 other wrecks, the final resting place for thousands of American, British, Australian, Dutch and Japanese sailors in the Java and South China seas and around the edges of the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

Only last month it was reported that the Chinese grab dredger Chuan Hoon 68 had recovered the wrecks of the British battleship HMS Prince of Wales and the battlecruiser HMS Repulse, sunk by Japanese bombers off the east coast of Malaysia in December 1941 days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, picked.

Director-General of the Royal Navy Museum, Dominic Tweddle, said in a May 24 statement that the illegal salvage operation has sharply highlighted the vulnerability of 5,000 similar historic underwater naval sites around the world to mass looting.

“We are saddened and concerned about the apparent vandalism for personal gain (of the two ships),” he lamented. “They are designated war graves. We are angry at the loss of naval heritage and the impact on the understanding of our Royal Navy history.

Tweddle said there is a need for a management strategy for the Royal Navy’s underwater heritage to better protect or memorialize the wrecks “including targeted retrieval of objects”.

“A strategy is essential to determine how to assess and manage these wrecks in the most efficient and effective way,” he said. “We must especially remember the crews who served on these lost ships and all too often gave their lives in the service of their countries.”

The HMAS Perth (I) arrives in Sydney Harbour, April 1940. Photo: Samuel Hood / ANMM Collection 00022409 / Australian National Maritime Museum

Retired Royal Navy captain Roger Turner, who led the recent successful search for the Japanese ship Montevideo Maru, which carried 1,000 Australian POWs to their deaths in 1942, told the Global Courant: “It is rather despicable that the Chinese are looting war graves . .”

Reflecting on the value of the scrap, the former nuclear submarine engineer points out that in one application, the 200mm-thick steel contains a very low level of absorbed radiation suitable for ultra-sensitive nuclear monitoring equipment.

“Steel from the post-nuclear era, since about 1940, carries its own radiation signal derived from above-ground nuclear weapons testing, which results in global radioactive fallout entering the steel during the smelting process,” he explains.

As a result, steel from the Repulse and Prince of Wales, launched in 1916 and 1939 respectively, is more valuable than normal scrap, especially the 400mm thick, high-performance armor covering parts of the 43,700-ton battleship.

Turner notes that while the anthropogenic element of background radiation has now fallen to what it was before the 1963 Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, which reduced the value of pre-nuclear era scrap, it still carries a premium.

“In relatively shallow water of about 68 meters, even without the nuclear bounty, 40,000 tons of steel at $100 a ton is a reasonable return,” he says. “It would probably be profitable to get just half of it.”

Malaysian authorities say they are investigating the movements of the 8,300-tonne Chuan Hong 68, which has been in Malaysian waters since February and is known for previous salvage operations in the Java Sea.

The ship is suspected of having also plundered the wrecks of the Dutch light cruisers Hr.Ms.

In 2017, in response to protests from the Dutch government, Indonesia declared the area around the three hulks a historic site, using rarely enforced legislation from 2010 to ban anchoring, fishing or diving.

However, it was too late to prevent the almost complete removal of the wrecks of the British heavy cruiser HMS Exeter and the destroyers HMS Encounter and HMS Electra, sunk in the same encounter with the loss of 2,300 lives.

Little is known about the wrecks of other Allied warships, including the corvette HMAS Armidale and the destroyer HMAS Voyager, both sunk off the south coast of East Timor, the aircraft carrier USS Langley (Cilacap) and the destroyers USS Edsall (eastern Indian Ocean), HMS Jupiter (Java Sea) and the HNLMS. Van Nes (Bangka).

Among the other hulls are three American submarines and two German U-boats, which operated from Japanese bases in occupied Dutch East Indies and British Malaya and were sunk in the Java Sea in November 1944 and April 1945.

Known Japanese wrecks include the heavy cruiser Ashigura, torpedoed off the Bangka-Belitung Islands in June 1945, a light cruiser, eight destroyers and three submarines, one of which is close to the Krakatoa volcano in the Sunda Strait.

British naval historian Geoffrey Till believes the ultimate solution is for the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) to create common conservation policies that can be implemented by individual nations.

“But given that countries don’t protect such sites of historic importance, and in many cases don’t have the resources to do so, even if they might care, it’s hard not to be desperately pessimistic about this,” he said.

It’s not clear how many commercial salvagers may be involved in the grave robbery, but naval experts blame some of the blame on complacent Western governments for allowing China’s gradual breach of international norms and conventions.

The looting of the Repulse and the Prince of Wales in 50m deep water at Kuantan is not new. In 2013, divers noticed that one of the Repulse’s bus-sized brass screws was missing, something that could only be done with a heavy crane.

Reports a year later claimed that explosives were used to break up both wrecks, the grave of 840 sailors. But the Malaysian government has done little to stop the destruction, despite the site being well within the country’s economic exclusion zone (EEZ).

The UK’s Protection of Military Remains Act makes it an offense to disturb a protected site or to disturb or remove anything from the site. Divers are allowed to visit but the rule is no touching and no penetrating.

However, there is no international law prohibiting the practice, and outside the United Kingdom the sanctions can in practice only be enforced against British citizens, British-flagged ships or ships landing in Great Britain.

HMAS Perth in the Battle of Sunda Strait. Image: AWM

Sunk by enemy gunfire and torpedoes on March 1, 1942, the Perth and the 9,000-ton Houston fell victim to the Japanese invasion force that had completed the conquest of Southeast Asia and was then occupying the Dutch East Indies.

Sailor Frank McGovern, who died last week at the age of 103, was the last survivor of the Perth. But that was just the beginning of his wartime ordeal, which Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese described as “great” and McGovern as “an extraordinary Australian”.

In the years following the sinking of the Perth, he endured two years on the infamous Burma Railway, then aboard a Japanese ship that was torpedoed by an American submarine in the Philippine Sea, while taking 1,000 prisoners of war to slave factories in Japan transported.

More than 540 Australians died, but McGovern and 30 other prisoners escaped and spent three days in a lifeboat before being picked up by another Japanese ship, which took them to Japan.

There McGovern was put to work in a factory, where his spine was broken in the second of two US air raids in which incendiary bombs destroyed large parts of Tokyo.

Forced to work or summarily executed, the fate that awaited the incapacitated after their blood was drained, he managed to survive until the Japanese surrendered on September 2, 1945.

McGovern was one of the first Australians to be repatriated home, but it took years for him to adjust, faced with many sad memories – including the death of his older brother aboard the ill-fated Perth.

The general location of the Perth and the Houston, which lost 700 crew in the sinking and subsequent Japanese internment, has long been known and is four kilometers apart close to the mouth of the strait separating Java and Sumatra.

Retired Australian Navy diver Clive Carlin and compatriot Jack Hammett spent many weekends searching for the two wrecks in 35m deep water, but say they only discovered their exact location in 1999 by a local fisherman using his own GPS.

“To me, the Perth is a memorial to the men who sailed in her, in defense of Australia and the Australian way of life,” said Carlin, a longtime Indonesian resident who helped lay a flag on the wreck during an underwater ceremony . on the 60th anniversary of the one-sided battle.

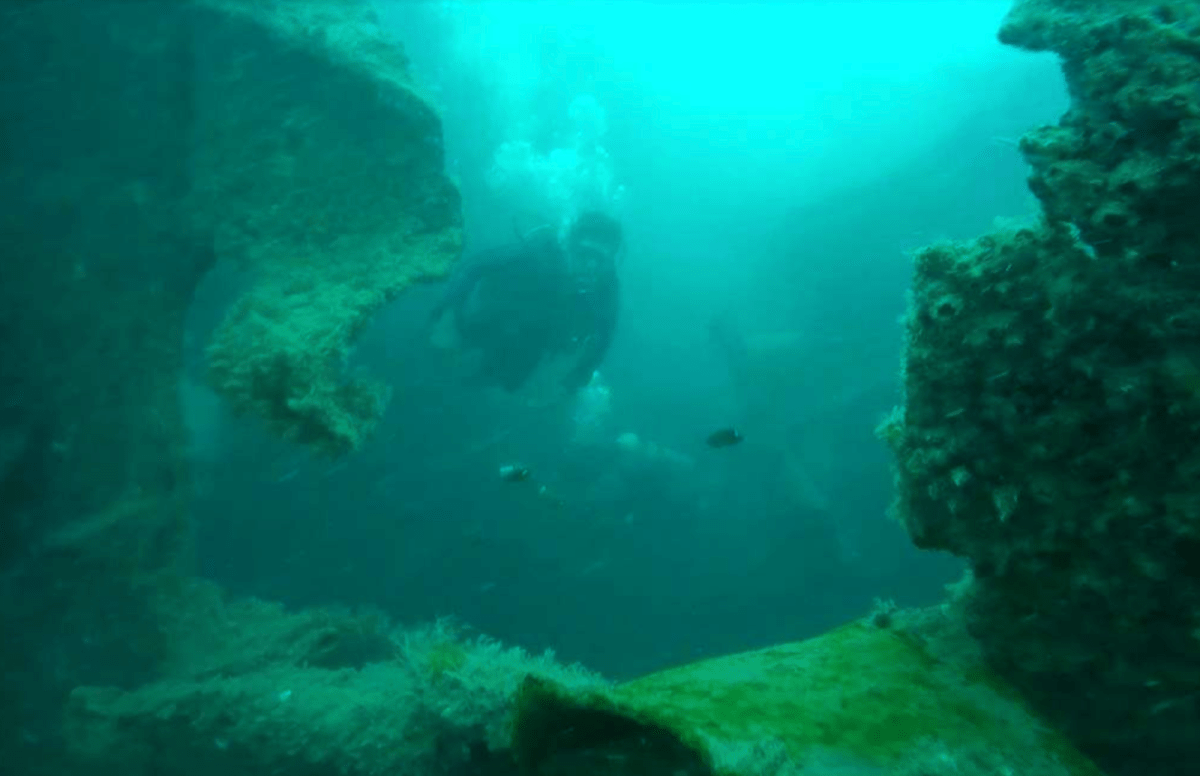

The shipwreck of HMAS Perth (I) lies in the waters between Java and Sumatra, a casualty of the 1942 Battle of the Sunda Strait. A joint research project between the museum and Pusat Penelitian Arkeologi Nasional (Indonesia) has documented the devastation that has caused by extensive illegal rescuing. Image: James Hunter, ANMM/Pusat Penelitian Arkeologi Nasional.

For the Australians, the issue of protecting the wrecks has resurfaced since the discovery of the Montevideo Maru, a converted passenger/cargo liner sunk off the northwestern Philippines by the US submarine Sturgeon in July 1942.

Nearly 1,000 Japanese-bound Australian POWs captured during fighting around the lightly defended Rabaul on the northern tip of New Britain in Papua New Guinea perished in what remains Australia’s worst maritime disaster.

The wreck is located about 100 kilometers west of Cape Bodjeodor in Luzon on a direct line to its planned destination on China’s Hainan Island. But at a depth of 4,000 meters — the same as the ill-fated Titanic in the North Atlantic — that’s unlikely to catch the attention of looters.

Similar:

Loading…