Global Courant 2023-05-30 15:48:41

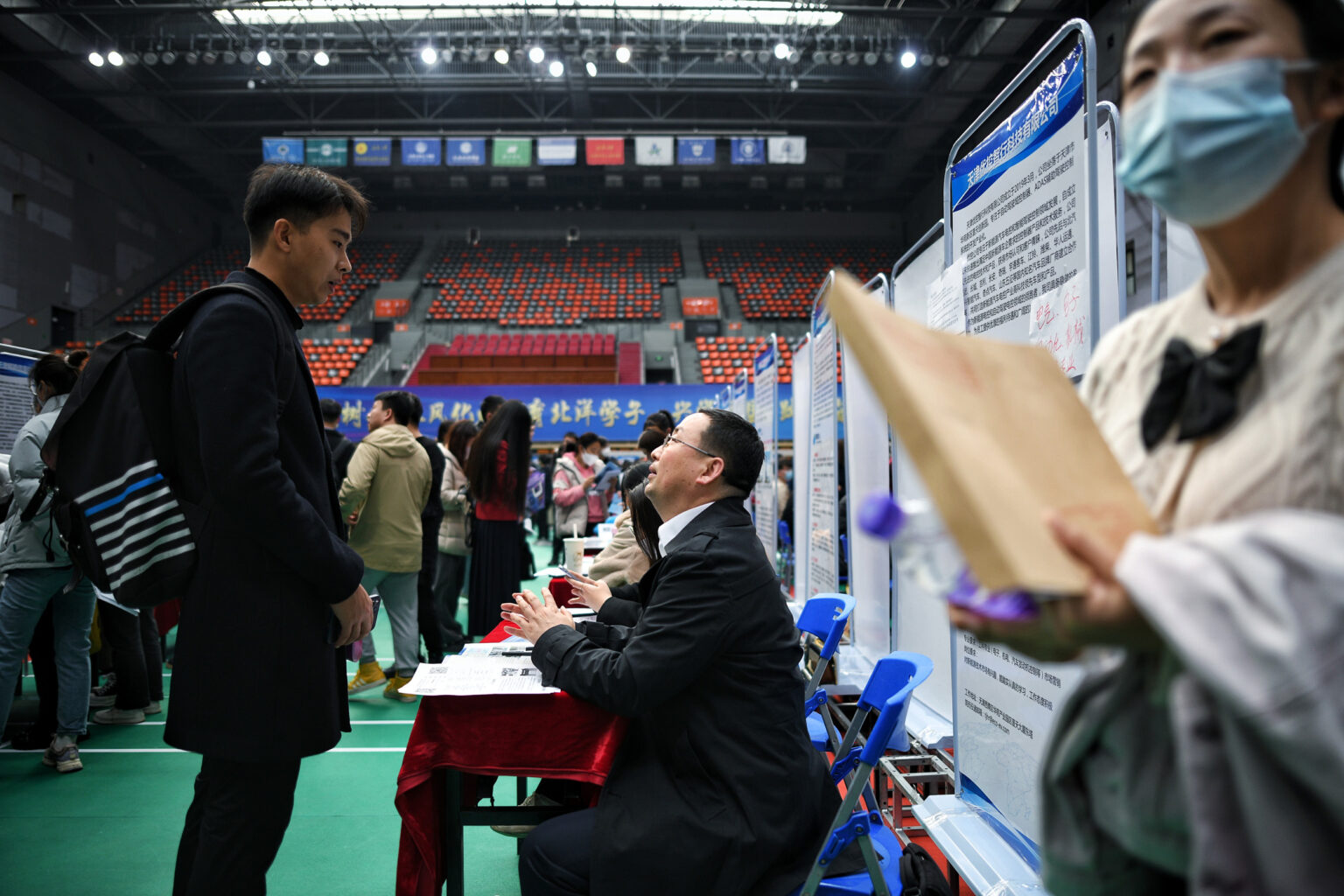

As youth unemployment in China rises to an all-time high, college graduates are caught in a perfect storm – some forced to take low-paying jobs or settle for jobs below their skill level.

Official data shows urban unemployment among 16-24 year olds in China hit a record 20.4% in Aprilabout four times the broader unemployment rate, while millions more college students are expected to graduate this year.

“This college bubble is finally bursting,” said Yao Lu, a sociology professor at Columbia University in New York. “The expansion of higher vocational education at the end of the 1990s led to an enormous influx of graduates, but there is a mismatch between supply and demand for highly skilled workers. The economy has not caught up.”

The scourge of underemployment is another problem facing Chinese youth and policymakers.

In a paper Lu co-authored with Xiaogang Li, a professor at Xi’an Jiaotong University, the professors estimate that at least another quarter of China’s college graduates are underemployed, on top of rising youth unemployment.

“Increasingly, college graduates are taking positions that are inconsistent with their education and credentials to avoid unemployment,” Lu told CNBC.

Underemployment occurs when people settle for low-skilled or low-paid jobs, or sometimes part-time work, because they cannot find full-time jobs that match their skills.

“These are the jobs that used to be mainly occupied by non-university graduates,” added Lu.

The scars of graduating in a tough economic time are well documented in other societies. Research from Stanford University shows that graduates who enter their working lives during a recession or economic downturn earn less for at least 10 to 15 years than those who graduate during periods of prosperity.

Furious accident?

Data from the Chinese Bureau of Statistics shows that 6 million of the 96 million 16 to 24 year olds in the urban labor force are currently unemployed. From this figure, Goldman Sachs estimates there are now 3 million more unemployed urban youth compared to the period before the Covid-19 pandemic.

This probably makes it more urgent for the Chinese government to act.

“Diminished job prospects can inevitably fuel dissatisfaction among the youth, and a perceived failure to ensure their material well-being can disrupt the social contract the Communist Party has with the people of China,” said Shehzad Qazi, chief executive of China. Beige Book.

Given China’s aging and declining population will reduce its economically active population, the impact of youth unemployment and underemployment “could potentially have very negative consequences for the economy,” Columbia’s Lu told CNBC.

While China is not the only society in the world plagued by double-digit youth unemployment, few others understand the magnitude of China’s problem, according to statistics from the International Labor Organization.

The Chinese central government is very aware of this problem.

In April, China’s State Council announced a 15-point plan aimed at better matching jobs with young job seekers. This includes support for skills training and internships, a commitment to a one-off increase in hiring in state-owned enterprises, and support for the entrepreneurial aspirations of graduates and migrant workers.

Structural mismatch

Addressing more fundamental mismatches is much more difficult, analysts say.

“In many societies, including China, there is usually a gap between the labor market and higher education institutions. They don’t necessarily talk to each other,” Lu said. “Universities have some idea of what the labor market situation is and what employers are looking for, but often their understanding is outdated and distorted from time to time.”

There is also a discrepancy between changing expectations of young people with higher education and an economy that is not keeping up with their ambitions.

“Due to the rapid increase in education, both for men and women, these young people are no longer willing to return to factory jobs,” said Jean Yeung, a sociology professor at the National University of Singapore.

Even as youth unemployment rises, China is almost projecting 30 million manufacturing jobs could run out of stock by 2025, according to the country’s Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security. That is almost half of all jobs in the sector, according to the ministry.

“But the plan was to transform China’s economy from a labor-intensive industry to a more technological, highly service-oriented knowledge economy,” Yeung added.

Yet, according to Qazi, this transition seems half-hearted in China’s state-driven economy.

Economists say a thriving service economy is based on support for the private sector. But the problem is that small and medium-sized companies cannot access credit.

“Until that happens, the private sector services won’t really be able to really absorb these young graduates who want to work in the new industries, the industries of the future, and then go through that massive economic transition.” Qazi said. “It’s all connected.”

Cyclic problems

China’s “zero Covid” policy during the pandemic led to factory closures and a two-month lockdown in the financial capital Shanghai last yearwhile the wider economy ground to a halt.

says Goldman Sachs the slack in the services sector at the beginning of the year, before China reopened, may have contributed to the current high youth unemployment.

However, US investment bank analysts estimate that youth unemployment in China is likely to peak in the summer months of July and August with the influx of recent graduates.

Goldman Sachs economists say China’s economic recovery would help get young people back to work as it would restore the consumer power of youth, a demographic that typically accounts for nearly 20% of China’s consumption.

Except the jobs may not match what they want or what they are trained for.

“I find it ironic that having a college degree is no longer enough to get a highly skilled job for most college graduates these days,” says Lu.

“But at the same time it becomes redundant because everyone gets it.”