Global Courant 2023-05-23 00:58:39

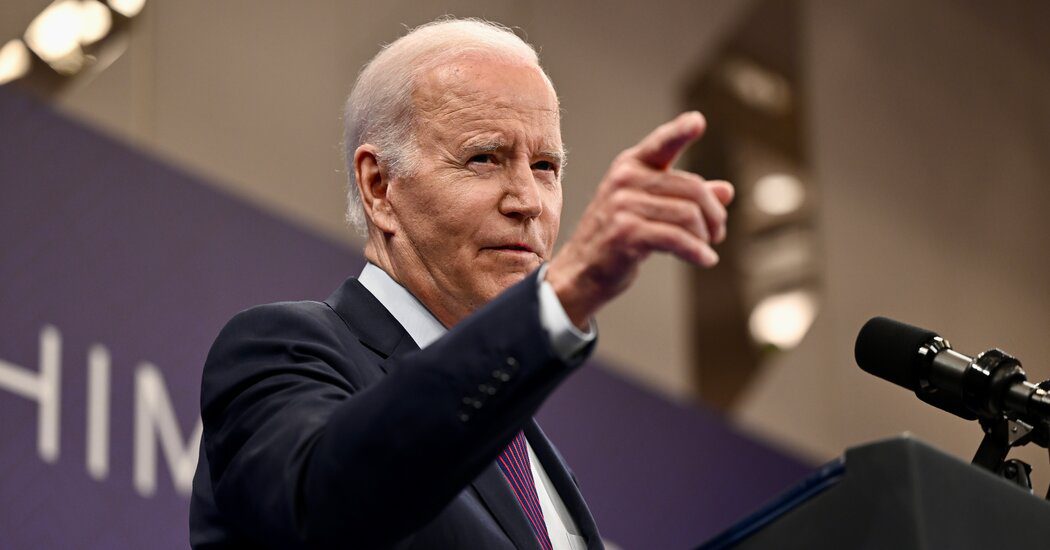

President Biden and his allies spent much of the G7 summit in Hiroshima, Japan, announcing new weapons packages for Ukraine, including a path to the delivery of F-16 fighter jets. They spent hours discussing strategy with President Volodymyr Zelensky for the next phase of a hot war started by Russia.

So it was easy to miss Mr Biden’s prediction on Sunday about a coming “thaw” in relations with Beijing as both sides move beyond what he called the “silly” Chinese act of sending a giant surveillance balloon over the United States, just the most recent in a series of incidents that have led to what appears to be a descent into confrontation.

It is much too early to say whether the president’s optimism is based on the silent signals he has received behind the scenes in meetings with the Chinese government in recent weeks.

Mr Biden’s own aides see a battle underway in China between factions seeking to resume economic relations with the United States and a much more powerful group aligning itself with President Xi Jinping’s emphasis on national security over economic growth. As this weekend showed, China is extremely sensitive to any suggestion that the West is staging a challenge to Beijing’s growing influence and power.

So if Mr. Biden is right, it may take some time for the ice to melt.

Facing a new, unified set of principles from key Western allies and Japan on how to protect their supply chains and their key technology from Beijing – contained in the meeting last communiqué — China erupted in outrage.

Beijing denounced what it portrayed as a cabal seeking to isolate and weaken Chinese power. The Japanese ambassador in Beijing was called in to investigate and China decided to ban products from Micron Technology, an American chip maker, because its products posed a security risk to the Chinese public. It seemed exactly the kind of “economic coercion” that world leaders had just promised to resist.

Mr Biden often says he does not want another Cold War with China to start. And he points out that the economic interdependence between Beijing and the West is so complex that the dynamics between the two countries are vastly different from when he first delved into foreign policy 50 years ago as a newly elected senator. .

The Hiroshima harmony on developing a common approach, and the Beijing explosions that followed, suggested that Mr Biden had made progress on one of his key foreign policy priorities, despite underlying tensions between the allies. Rather than dwell on their differences, the leaders of the major industrial democracies have framed their approach to China in a way that Beijing clearly saw as potentially threatening, some analysts noted after the meeting.

“An indication that Washington would be happy is that Beijing is so dissatisfied,” said Michael Fullilove, the executive director of the Lowy Institute, a research group in Sydney, Australia.

Matthew Pottinger, deputy national security adviser to President Donald J. Trump and the architect of that administration’s approach to China, agreed. “The fact that Beijing has been so touchy about the G7’s statements is an indication that the allies are moving in the right direction.”

Mr Biden and the other G7 leaders – including Britain, Canada, France, Germany, Italy and Japan – wrote their first joint statement of principles on how they would resist economic blackmail and deter China from threatening or entering Taiwan. as they tried to reassure Beijing that they were not seeking confrontation.

The communiqué pressed China’s usual points of stress, including the military buildup in the South China Sea and widely documented human rights violations against Uyghurs and other Muslims in Xinjiang. Four months after the United States quietly began disseminating intelligence to its European allies suggesting that China was considering sending arms to Russia to fuel its fight in Ukraine, the document appeared to be a warning to Beijing to include its “no borders” relationship with Russia. far.

But the democracies also left the door open to improving relations with Beijing by making it clear that they were not trying to contain a Cold War strategy against the world’s emerging economy, even as they tried to cut off China from key technologies – including the European-made machines that are essential for the production of the most advanced semiconductors in the world.

“Our policy approaches are not designed to harm China, nor do we seek to thwart China’s economic progress and development,” the statement said. “A growing China abiding by international rules would be of global importance. We are not disconnecting or turning inward. At the same time, we recognize that economic resilience requires less risk and diversification.”

“De-risking” is the new art term created by the Europeans to describe a strategy to reduce their dependence on Chinese supply chains without “decoupling”, a much stricter separation of economic relations. Mr Biden’s team has embraced the phrase and the strategy – meant to sound self-protective rather than punitive – has become a staple of recent conversation about how to deal with Beijing. Jake Sullivan, the national security adviser, talks about “building a high fence around a small yard” to describe the protection of key technologies that could support China’s rapid military buildup.

But what looks like risk reduction to the United States and Europe may look like a well-crafted containment strategy in Beijing.

The consensus reached in Hiroshima came after what Michael J. Green, a former top Asia adviser to President George W. Bush, called “a series of diplomatic wins for the US and losses for China.” He has been working behind the scenes on rapprochement between South Korea and Japan, and plans to integrate Japan into a consultative group on nuclear strategy and deterrence announced last month by South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol during a state visit. If successful, it would establish a much closer nuclear alliance near China.

“From Beijing’s perspective, this has been a week in which the other powers in the region have aligned even more closely with the United States,” said Mr. Green, now the general director of the United States Studies Center at the University of Sydney.

China pushed back hard. In a statement issued over the weekend, it accused the G7 of “obstructing international peace”, “defaming and attacking China” and “grossly interfering in China’s internal affairs”. That same day, it accused Micron of “relatively serious cybersecurity problems” that could threaten national security, the same argument the United States makes about TikTok and Huawei.

Despite the common base in Hiroshima, Mr Biden’s decision to cancel the second half of his Pacific trip, including a stopover in Papua New Guinea, so he could hurry home to cover domestic spending and deal with debt negotiations, considered a setback. in competition with China.

Now the question is whether Mr. Biden can quietly mend a relationship with Mr. Xi that seemed to turn around last fall, after their first face-to-face meeting.

Mr Biden referred to the spy balloon incident in interesting ways on Sunday.

“And then this silly balloon with spy equipment flew over the United States in two boxcars, got shot down and everything changed in terms of talking to each other,” he said. “I think you’ll see that start to thaw very soon.”

If there is a turnaround, it could be due to Sullivan’s quiet talks in Vienna this month with Wang Yi, China’s top foreign policy official.

The sessions were barely warm, but in some ways they were more candid and helpful than US officials expected. Rather than simply a recitation of talking points, as is typical in encounters with Chinese counterparts, Mr. Wang in more unscripted terms than usual, according to officials familiar with the conversations. Grievances were raised on both sides that the Biden team hoped would help clear the air.

Long talks were held in particular about Ukraine and Taiwan. Mr. Wang stressed that China was not seeking conflict with Taiwan, apparently to appease US officials who feared last summer that China would accelerate its plans to resolve its dispute over Taiwan by force.

Mr. Wang raised the need to avoid rushing elections in Taiwan early next year. Mr Sullivan stressed that China’s own behavior was raising temperatures and increasing the risk of escalation.

Administrative officials hope to return to a more regular dialogue with China, perhaps sending Treasury Secretary Janet L. Yellen and Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo to China, eventually rescheduling a trip to Beijing from Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken, who canceled a visit after the spy balloon delivery. There is talk of a meeting between Mr Biden and Mr Xi in the fall.

But the war in Ukraine will continue to overshadow the relationship — and so will the relationship between Moscow and Beijing, what one of Biden’s aides calls “the alliance of the injured.” But for now, US officials have taken solace that China, to their knowledge, has not supplied deadly weapons to Russia, despite President Vladimir V. Putin’s need for armaments.

David Pierson contributed reporting.